Counting the Invisible: How Patent Valuation Turns Intangibles into Strategy – MIPLM Module 2

In today’s innovation economy, patents and other intellectual property have quietly become the real infrastructure of value creation. Factories, machines and buildings still matter, but much of a company’s competitive edge now lies in code, data, algorithms, brands and protected technologies. That’s why value-oriented IP management treats IP not as a legal afterthought, but as a strategic asset class that must be assessed, compared and steered just like any other investment. The article Value-Oriented IP Management argues that management can only do this if reliable value information is available for key patents and portfolios.

At the same time, the financial system still struggles to “see” this value. Traditional balance sheets recognise purchased patents and acquired goodwill, but most self-created intangible assets never appear at all. As explained in The Hidden Power of Balance Sheets, this creates an “intangible asset dilemma”: economically decisive IP sits off-balance-sheet, while the official accounts suggest a much more asset-light business than actually exists. For IP management, that gap is dangerous—because decisions about filing, maintaining, enforcing or licensing patents must often be made against incomplete or misleading financial information.

At the same time, the financial system still struggles to “see” this value. Traditional balance sheets recognise purchased patents and acquired goodwill, but most self-created intangible assets never appear at all. As explained in The Hidden Power of Balance Sheets, this creates an “intangible asset dilemma”: economically decisive IP sits off-balance-sheet, while the official accounts suggest a much more asset-light business than actually exists. For IP management, that gap is dangerous—because decisions about filing, maintaining, enforcing or licensing patents must often be made against incomplete or misleading financial information.

Value, valuation and scenarios as the real “object”

Before we can value a patent, we need clarity about what “value” actually means. In economics, three concepts must be separated: cost, price and value. The lecture on patent valuation and the piece Cost, Price, and Value – Key Economic Concepts make this distinction very explicit.

- Cost describes the consumption of resources (including R&D spending) needed to create or use an asset.

- Price is the outcome of a negotiation or market transaction at a specific moment.

- Value is the discounted stream of future economic benefits that an asset can generate in a given situation.

Valuation, in this sense, is the process of translating expectations about future benefits into a present value, given assumptions about time, risk and the specific decision context. The lecture emphasises that we never value a patent “in the abstract”. Instead, we value a scenario: who owns the patent, which complementary assets are available, which markets exist, what strategic options are open, and what competitors might do.

So the practical “object” of valuation is not just the legal right, but a patent-plus-context scenario: “this patent, in this company, under these strategic plans, in this competitive and regulatory environment.” Change the scenario, and the value changes.

From invisible intangibles to value-oriented IP management

This scenario logic is central to value-oriented IP management. The article Value-Oriented IP Management shows that IP decisions (file, maintain, enforce, license, contribute to a joint venture, use as collateral, etc.) are ultimately investment and portfolio questions. Management needs to understand:

- Which patents actually move the needle for revenue, margin, or strategic positioning.

- How different strategic scenarios (own exploitation vs licensing vs sale) would affect value.

- Where marginal IP investments add value—and where they are just sunk cost.

Because most self-created IP assets do not show up transparently in financial statements, IP management must build its own internal “shadow balance sheet” of patent-based value. The Hidden Power of Balance Sheets describes how traditional accounting under-reports intangibles and why investors increasingly complement official balance sheets with their own analyses of IP, data and know-how. IP valuation is the missing link between legal rights and this internal economic picture.

A good overview of how intangible assets shape corporate performance is given in the lecture and the video on Intangible Assets in Enterprises, which show how brand, technology and data often explain more of firm value than physical assets. Together they underline why IP valuation is not a niche exercise but a prerequisite for serious strategy.

The 2012 puzzle of Chinese investments – and what we know in 2025

In the 2012 film Intangibles Become the Prime Investment Target, the narrator points to a “riddle”: why were Chinese and other Asian investors pouring money into companies that seemed to lack tangible assets, yet commanded high valuations? At the time, this looked mysterious from a traditional balance-sheet perspective.

Seen from 2025, the riddle has largely dissolved. Chinese firms have built enormous stocks of intangible assets—especially patents—in sectors like telecommunications, consumer electronics, batteries and AI. Their investment flows were not irrational; they were buying strategic positions in technologies and platforms whose economic potential was not yet visible in classic accounting terms. The surge of Chinese patent applications and the build-up of standards-essential portfolios are now well-documented signals of this strategy.

This is a powerful reminder that capital markets already price IP-based scenarios, even when balance sheets don’t. For IP experts, the lesson is clear: if you cannot articulate and quantify the patent-based scenario behind an investment, someone else will, and they will set the terms.

Economic characteristics of intangible goods

Valuing patents is not just “harder accounting”; it requires understanding how intangible goods behave economically. The lecture and the video on Economic Characteristics of IP highlight several key features.

- Non-rivalry in use: Using a patent in one factory does not prevent using the same know-how elsewhere, as long as capacity and market demand exist.

- Scalability: Once the underlying technology exists, additional output often requires far less incremental investment than the original R&D.

- Sunk costs: Most R&D and filing costs are sunk and cannot be recovered if the project fails or the patent is not used.

- Inverse depreciation: Some IP assets gain value through use—brands that become stronger, or patented technologies that evolve into industry standards.

These characteristics explain why IP portfolios can suddenly “tip” into very high value when a standard emerges or a platform succeeds. They also explain why cost-based valuation is often misleading: high R&D spending does not guarantee high value, and low spending does not imply low value.

Two fundamental value concepts: value-in-use and transfer value

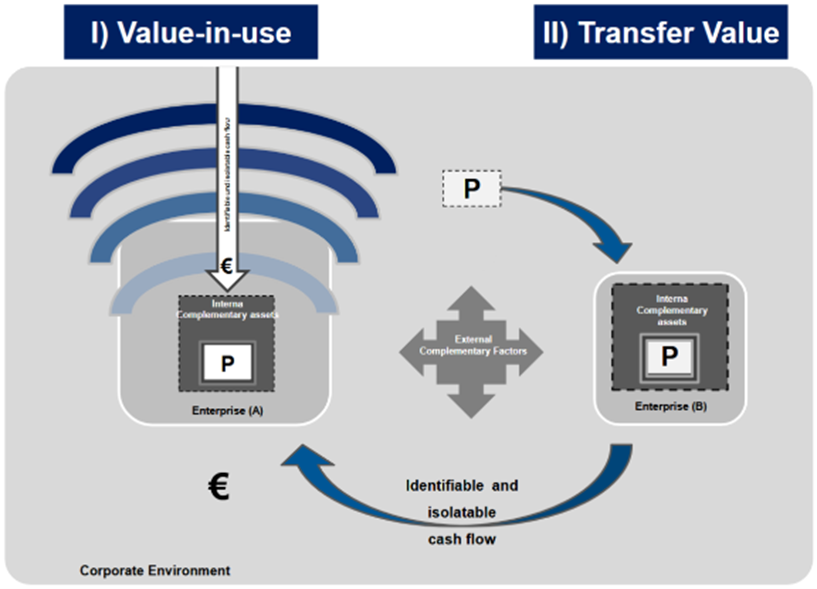

The lecture distinguishes two fundamental value concepts for patents: value-in-use and transfer value.

- Value-in-use asks: What is this patent worth to this specific company, given its business model, complementary assets and strategy? Here, the patent is one piece in a larger system: production facilities, brand, sales channels, regulatory approvals and so on. The value-in-use is the additional economic benefit the company can realise because it owns and uses the patent within that system.

- Transfer value asks: What would a third party be willing to pay for this patent in a transaction? This requires not only understanding potential buyers’ business models and complementary assets, but also observable or simulated market transactions.

In value-oriented IP management, both concepts matter. For internal decisions—such as whether to maintain, enforce or integrate a patent into a platform—the value-in-use is central. For licensing, IP-backed lending or M&A, transfer value becomes more important. A sophisticated IP strategy will explicitly consider both and understand how they diverge across scenarios.

In value-oriented IP management, both concepts matter. For internal decisions—such as whether to maintain, enforce or integrate a patent into a platform—the value-in-use is central. For licensing, IP-backed lending or M&A, transfer value becomes more important. A sophisticated IP strategy will explicitly consider both and understand how they diverge across scenarios.

Approaches to patent valuation

The lecture’s overview of valuation approaches and the article Understanding IP Valuation structure patent valuation into three main direct approaches.

- Cost approach

Here, the patent is valued based on the costs required to recreate or replace the protected technology: historical R&D, replacement costs, or costs avoided by owning the patent. It is sometimes useful as a lower bound, but it ignores market demand, competitive advantage and strategic effects. - Market approach

This approach compares the patent with similar assets for which transaction prices are known: license agreements, patent sales, portfolio deals. Typical procedures include price comparison, comparative profit methods or profit-split analyses. The challenge is finding sufficiently comparable transactions and adjusting for differences in scope, legal status and market context. - Income approach

The income (or revenue) approach values the patent as the discounted present value of future economic benefits. These benefits may be direct (royalty income, price premiums) or indirect (cost savings, stronger bargaining power, access to markets). Methods include the relief-from-royalty approach and discounted cash flow (DCF), where expected patent-related cash flows are discounted with a risk-adjusted rate such as WACC.

For value-oriented IP management, the income approach is usually the workhorse, because it connects patent protection directly to value drivers in the business model.

Log-normal value distribution in patent portfolios

An important empirical insight from patent valuation practice is that portfolio value is not evenly distributed. The video on Patent Portfolio Value Distribution uses a log-normal curve to show that a small fraction of patents contribute the majority of economic value, while many patents have little or no measurable impact.

In a log-normal distribution:

- Most patents cluster at low values.

- A “long tail” contains a few high-value patents—the crown jewels.

- Synergies between patents (clusters, families, standards positions) further skew the distribution.

For value-oriented IP management, this has two consequences. First, it justifies investing serious effort into identifying and managing the top few percent of patents where enforcement, licensing or strategic partnerships can create disproportionate returns. Second, it supports rigorous pruning of low-value assets to avoid wasting maintenance fees and management attention.

Objective, subjective and objectified values

The lecture and the video on Objective Values, Subjective Values and Objectified Values make a provocative point: objective values do not exist in IP valuation. There is no single “true” value of a patent independent of perspective and context.

Instead, we distinguish:

- Subjective values: These are decision values for a specific actor in a specific scenario—the value-in-use for one company, or the maximum price a particular buyer would pay. They are “right” if they are internally consistent with that actor’s expectations and constraints.

- Objectified (typified) values: These are standardised, intersubjectively verifiable values determined using typification methods, as described in Determining Typified Asset Values. They are designed to be comparable across assets and situations, often for financing, accounting or regulatory purposes.

Subjective values are highly relevant for concrete strategic decisions but not easily comparable; objectified values are comparable but may be far removed from the specific decision context. The blog on typified values and the IP valuation lecture both stress that decision-makers must be clear which type of value they are using and for what purpose.

Uncertainty versus risk

Innovation is full of unknowns: technology performance, market adoption, regulatory shifts, competitor reactions. The video on Uncertainty vs. Risk and the lecture’s theme “Navigating Uncertainty in Innovation” draw a crucial distinction:

- Risk means we can assign probabilities to different outcomes (e.g. market share scenarios, royalty rate ranges) based on data or reasonable assumptions.

- Uncertainty means we cannot reliably assign probabilities at all.

In patent valuation, risk can be handled with probability-weighted cash flows, scenario trees or Monte-Carlo simulations. Uncertainty, by contrast, often requires explicit scenario analysis: building several coherent narratives (optimistic, base, pessimistic, disruption scenarios) and understanding how sensitive the patent value is to each. This again reinforces why the scenario is the real object of valuation—and why value-oriented IP management should treat valuations as living models that are updated as uncertainty turns into quantifiable risk.

The ten steps of the valuation procedure

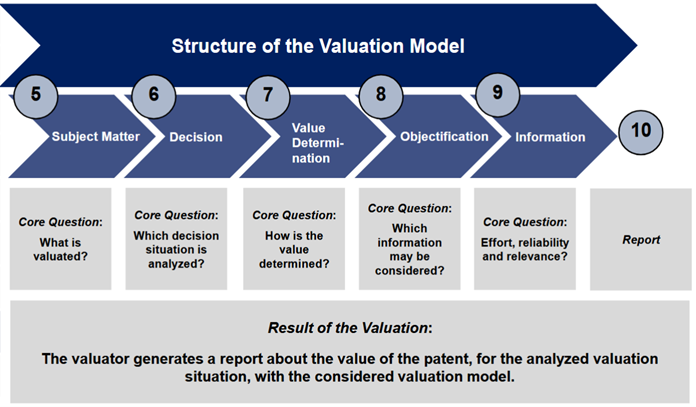

The lecture breaks the valuation procedure into ten logical steps, grouped into two major phases: analysis of the valuation context and construction of the valuation model.

Phase 1: Analysis of the valuation context (Steps 1–4)

1. Valuation cause – Why is the patent being valued?

Is the trigger management-oriented (portfolio steering, R&D prioritisation), enterprise-related (M&A, joint venture), transfer-oriented (licensing, sale), conflict-based (litigation, damages), or financing/accounting-related (collateral, purchase-price allocation)? The cause determines which economic effects matter most.

2. Valuation purpose – What is the valuator’s role?

Are they advising management, mediating between parties, supporting a negotiation, or acting as a neutral expert? The purpose shapes the degree of subjectivity allowed and the acceptable methods.

3. Valuation goal – Which information is considered?

Here, the valuator clarifies which data, assumptions and perspectives may enter the model. A purely management-oriented valuation will incorporate the company’s own plans and expectations; a neutral expert opinion for court may need to rely more on publicly verifiable information and typified values.

4. Valuation addressee – Who receives the value information?

Internal management, shareholders, lenders, licensees, tax authorities, courts—each addressee has different expectations about documentation, objectification and acceptable ranges. The analysis of the valuation context is complete when the valuator fully understands cause, purpose, goal and addressee.

Phase 2: Construction of the valuation model (Steps 5–10)

5. Valuation subject matter – What exactly is valued?

Is it a single patent, a family, a cluster, or an entire portfolio? Which territories, claims and remaining terms are in scope? Are we valuing value-in-use for a specific company, or transfer value for a potential buyer? This step defines the boundary of the valuation object and the relevant complementary assets.

6. Decision situation and value concept – Which decision is analysed?

The valuator models the decision problem (e.g. “maintain vs. abandon”, “license vs. keep exclusive”, “sell vs. contribute to JV”) and chooses the appropriate value concept (value-in-use vs transfer value, subjective vs objectified). This step ensures that the valuation is anchored in a concrete decision, not an abstract number.

7. Value determination – How is the value calculated?

Based on the chosen concept and decision model, the valuator selects a valuation method (cost, market, income approach; DCF, relief-from-royalty, option models) and specifies the mechanics: observation period, cash flow attribution, discount rates, royalty rates, growth assumptions, etc.

8. Objectification – How is subjectivity handled?

Here, the valuator decides how far to typify or standardise assumptions: for example, using market-based royalty rate ranges, industry-standard discount rates, or reference portfolios. The article Determining Typified Asset Values shows how such objectification can improve comparability, especially when valuations are used for financing or regulatory purposes. (IPBA® Connect)

9. Information – Which data and evidence are used?

The valuator identifies and documents all information sources: market studies, internal business plans, legal opinions on patent validity and scope, cost data, competitor portfolios. The lecture stresses that effort, reliability and relevance of information must be balanced; not every possible data point is worth collecting, but key value drivers and risks must be backed by solid evidence.

10. Report – How are results communicated?

Finally, the valuator prepares a report that presents the valuation result for the analysed scenario, explains the chosen model and methods, documents assumptions and sensitivities, and clarifies the limitations of the result. This step is crucial for value-oriented IP management: only a well-documented valuation can be challenged, updated and integrated into broader strategic and financial processes.

Why all this matters for value-oriented IP management

Put together, these concepts turn patent valuation from a one-off number-crunching exercise into a management tool:

- The distinction between value-in-use and transfer value helps decide whether a patent should be exploited internally, licensed out, or sold.

- The recognition that objective values do not exist but objectified values are useful for comparability keeps expectations realistic while still enabling standardisation where needed.

- The log-normal value distribution of portfolios supports focused resource allocation to high-impact patents.

- The explicit modelling of uncertainty versus risk, and of different scenarios, makes valuation robust enough to guide decisions in dynamic markets.

- Above all, the ten-step valuation procedure ensures that every valuation is traceable back to its strategic purpose, information base and decision context.

In a world where balance sheets still hide much of the true economic power of self-created intangibles, value-oriented IP management needs precisely this kind of structured, scenario-based valuation to align legal rights, business models and capital allocation.