IP and Hallucinogens – is it possible?

The blog provides an overview of the overlapping IP and ethical issues on the use of hallucinating substances such as LSD, psilocybin, MDMA etc. for psychedelics therapies.

Mental illness is not restricted to any country and can affect anyone’s regular life. According to the WHO, anxiety and depression are the most common mental health issues that affect about 2.8 million people globally. Psychedelics therapy is the use of plants and their compounds to induce hallucinations for treating mental health issues such as depression, anxiety and PTSD.[1] LSD, MDMA and DMT are some common hallucinogens administered by medical practitioners to treat patients.[2] The growing use of psychedelic therapies has exposed the life-science industry to a plethora of challenges to their IP rights.

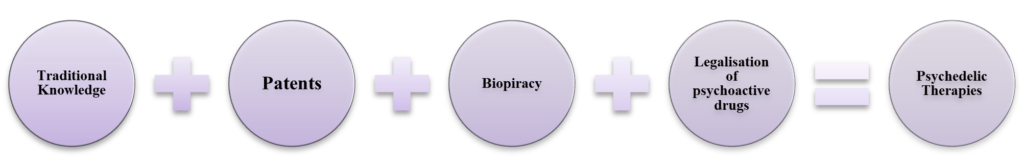

The use of mushrooms for psychedelic therapies is an age-old tradition of the Mazatec tribe, a Mexican tribe based in Oaxaca, Southwest Mexico. In 1955 through an Article, R. Gordon Wasson introduced the West to mushrooms for treating mental health illnesses and also coined the term magic mushroom. Psilocybin is a natural prodrug compound present in more than 400 documented varieties of mushrooms.[3] According to Psilocybin Alpha, an organisation that dedicates its analysis to the emerging psychedelic medicine sector highlights from 2019 to 2021, 43 psilocybin patents were filed in the US. Further in Europe, life-science organisations are conducting human clinical trials on psilocybin. Magic mushroom is one of the examples of many psychedelics derived from natural compounds of psychoactive drugs. The regulatory overlap in the life-science industry is complex. The chart and explanation below provide an overview of complex legal parameters that surround psychedelic therapies.

- Traditional Knowledge

Traditional Knowledge is attached to cultural, spiritual and community beliefs passed down to each generation. It is neither an IP created nor novel but is intellectual traditions and culture. According to 1982 estimates, 50% of the US pharma patents were derived from natural substances that generated a sale of 20 billion.[4] Article 1 of the Nagoya Protocol, preserving the traditional knowledge, states that biological diversity shall be conserved and used sustainably by fair and equitable sharing of genetic resources.[5] Further, Article 27 of TRIPS states that a plant variety can be protected by a patent or with a system created for sui generis purpose.[6] Interpreting the international provisions from the perspective of psychedelics, only genetically modified or artificially produced varieties can be patented.

- Patents

Psychedelic plants are produced naturally and not in laboratories. The US psychedelic sector is valued at $10.75 billion by 2027. Patents on psychedelic therapies concern legal and ethical aspects of traditional knowledge. Polymorphs are the variations of the existing compound that have been recommended to be excluded from patents by the United Nations. Prodrugs are the compounds that are naturally present and due to enzymatic reactions become active only inside the body. Patents on polymorphs and prodrugs are much of a debatable issue within the industry as they are already a part of a drug molecule and applied as secondary patents for a longer patent term. According to the European Commission Pharmaceutical Inquiry Report, the secondary patents filed are more than the primary patents of the bestselling medicines.[7] Thus, it leads to the evergreening of patents and commercialising the traditional knowledge.

- Biopiracy

Biopiracy is defined as commercially exploiting the knowledge and naturally occurring resources by patents without compensating the communities from which that originates. It is an IP infringement of traditional knowledge by patents. Opium is a naturally occurring substance used by indigenous communities across the globe for various medicinal purposes. Morphine is an active component derived from opium and is prohibited in most countries. Opium and morphine are classified as psychotropic and narcotic drugs in most jurisdictions. However, derivatives of opium and morphine are used in medicines such as Tylenol with codeine. Thus, the complexity of pharmaceutical patents is an overlap of naturally occurring compounds and recognizing the efforts of the communities if it involves traditional knowledge of medicines.

- The legalisation of psychoactive substances

The use of psychoactive compounds in medicines has also challenged organisations to look at regulations on psychoactive substances. According to the WHO, the psychoactive substance may consist of both legal and illegal substances. Sergio Oliveros, psychiatrist and psychotherapy specialist explains that ‘…between 1950 and 1967 its effects on depression, anxiety and addictions were studied. But then it was declared illegal.’[8] Decriminalisation of psychoactive substances is still a debatable topic among the legislatures that impacts the R&D of the pharma industry. The stigma attached to psychoactive substances creates hurdles for scientists. A clinical study conducted by Bouso that was approved by Spain’s Ministry of Health and funded by the US in 2002 was shut down, which is an example of such stigma that still exists.

To conclude, the blog summarises the complex IP and ethical issues on the psychedelic therapies and the use of psychoactive substances in medicines.

About the blogpost author:

Trishala is a Junior Legal Counsel at the GSK, India. She has completed a postgraduate degree in IT and IP law from the University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK. Her areas of personal interests is analysing inter-disciplinary subject matters related to IP and developing technologies such as blockchain and AI.

Trishala is a Junior Legal Counsel at the GSK, India. She has completed a postgraduate degree in IT and IP law from the University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK. Her areas of personal interests is analysing inter-disciplinary subject matters related to IP and developing technologies such as blockchain and AI.

The assumptions, views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author in her personal capacity and do not in any manner reflect or represent any policy, position, opinion, view or idea of GSK.

_______________________

[1] Zawn Villines, ‘What to know about psychedelic therapy’ MedicalNewsToday 2021 <https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/psychedelic-therapy > accessed 21 March 2022

[2] Anonymus, ‘Therapy with MDMA? Experts debate the use of psychedelic drugs in medical treatment’ Science and Tech, El Pais < https://english.elpais.com/science-tech/2022-03-27/therapy-with-mdma-experts-debate-the-use-of-psychedelic-drugs-in-medical-treatment.html > accessed 04 April 2022

[3] Gael Girón S. Lang B. LeMaster S. Matthews K. McAllister S. Denver Psilocybin Mushroom Policy Review Panel. City and County of Denver. 2021 Comprehensive Report. Denver, CO, USA

[4]Jack Kloppenburg Jr., No Hunting! Biodiversity, Indigenous Rights, and Scientific Poaching (15 Cultural Survival Q., 1991) as quoted in Murray Lee Eiland, Patenting Traditional Medicine (Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH., 2018) 8

[5]Nagoya Protocol on access to genetic resources and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from their utilization, 2010

[6]TRIPS Agreement, 1995 art 27(3)

[7] European Comm’n, Pharmaceutical Sector Inquiry Report (2009), http://ec.europa.eu/competition/sectors/pharmaceuticals/inquiry/staff_working_paper_part1.pdf.

[8] ibid[2]