IP Lessons from Vintage Tech

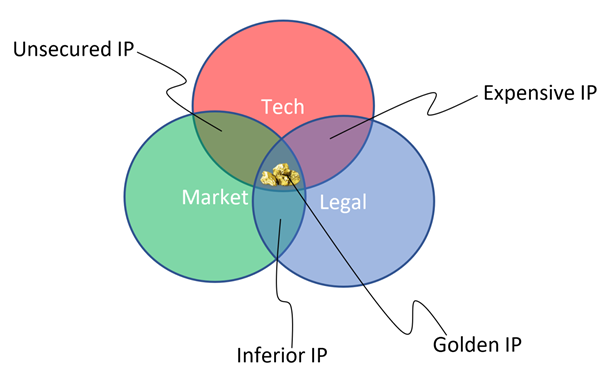

All IP is not valuable IP. In industry there are three essential components to valuable technical IP, i.e., Technology, Legal and Market. The latter one happens to be perhaps the prime reason why IP rights exist in the first place. As seen in FIG. 1, the so-called “golden nuggets” of IP lie at an intersection of the three components.

An IP with weak market focus may be Expensive IP. Even though the technical solution provided with such IP may be a superior one and it may be protected in the best way possible, such IP may be market irrelevant due to cheaper solutions which are just “good enough”. Alternatively, the technical solution covered by the Expensive IP may be far away from what the market really wants. There, thus, needs to be a proper understanding of the market for placing IP rights which are properly aligned with the market needs.

An IP with poor technology basis may be Inferior IP. This kind of IP may focus on a technical solution which is poorer than what the competitors are offering. Even though an IP right covering such IP may be good and it covers its own market well, such an IP may be simply not technically competitive, thus irrelevant for the competitors. An improvement of this function lies in the R&D domain of the company.

An IP with poor legal coverage may be Unsecured IP. Even though the technical solution may the best there is and there is good demand in the market for the solution, such an IP may be exposed to unauthorized copying by being inadequately secured. This IP may thus be a free-buffet for the competitors who can exploit it without the costs borne for the technical development of the solution. An improvement of this function lies more in the legal function of the company.

Those who have worked in an in-house role will recognize that if left alone, such an alignment as shown in FIG. 1 does not consistently occur without intervention. An important way to handle it is by raising IP awareness in the organization. A savvy IP professional will often lead change in this domain by bringing the business and R&D functions in an alignment to be able to pick out valuable IP rights at the right time.

To this end, an example is due to support this strategy.

Many of the readers will recognize the name gramophone (or phonograph). It is one of the inventions which are credited to Edison. Edison, as many will know, was a prolific inventor and user of the patent system. Those of you who have never had an opportunity to open one of these machines and see how it works, I can tell you that it is amazingly simple. The device comprises a simple mechanical motor which rotates a platform at a constant speed. For producing sound, the device comprises a diaphragm which receives and amplifies vibrations produced by a needle when the needle experiences “bumps” in the groove of a record which is being rotated on the platform. I am sure most of you have seen flat disc-shaped records, but Edison chose to use cylindrical ones. Indeed, the machines which he produced and sold played hollow cylinders with grooves on the outer surface. For playing, the hollow cylinder would be loaded over a cylindrical platform. An advantage of the cylindrical shape is that the needle always experiences constant linear velocity irrespective of the location along the length of the record. Even though Edison was aware that disc-shaped record would also work, he decided to concentrate on cylindrical records because they were technically superior to discs.

By ignoring the disc form, Edison made a mistake of not understanding the market needs. He ignored, for example, that the discs can be easier to manufacture as compared to hollow cylinders. Additionally, discs are easier to store as well. Disks thus had advantages spanning throughout the value chain, i.e., cheaper to manufacture, cheaper to ship and store – both for the supplier as well as for the customer. The market thus evolved to side with disc records, which happened to be just “good enough”. To Edison’s disadvantage, no royalties were due to him by disc manufacturers as the technology was “different enough” from his.

Edison’s case would thus lie in a hybrid of the “Expensive IP” and “Unsecured IP” categories. He did own rights to the best technology, but not the technology which the market needed. He did have knowledge of the alternatives, but did he not secure those aspects to be able to stop his competitors. This is a good example of how technology-centric brilliance can sometimes overshadow market-oriented thinking.

Lessons to be learned:

1. Think/plan for the entire value chain

- Consider not only what works well technically, but also what works best for most of the value chain

- Keep user/customer in front and center

2. If possible, try to secure whatever “works”

- Not only what is technically superior

3. Involve also business functions such as marketing and sales in forming a well-rounded IP strategy.

____________________

Fine print: The views expressed above are the author’s own. The text is not intended to provide you any legal advice, and nor does it create an attorney-client relationship with you. The information provided is without any representation or warranty of any kind. The examples provided are dependent upon facts of the particular matters. No assurance or guarantee of any kind is thus provided. No liability is accepted.

About the blogpost author:

Dr. Tajeshwar Singh is an IP professional with real-world technical, management and commercial experience in electronics, ICT, instrumentation and sensors. He earned recognition in IAM Patent 1000 grade in 2019 during private practice.

Dr. Tajeshwar Singh is an IP professional with real-world technical, management and commercial experience in electronics, ICT, instrumentation and sensors. He earned recognition in IAM Patent 1000 grade in 2019 during private practice.

Prior to entering the IPR domain, he has been an electronics hobbyist, power-plant engineer, researcher, chip designer, inventor, R&D manager, analog circuit design specialist and system architect. A unique combination of engineering skills and patent expertise enables him to provide effective counseling of agile engineering teams and harvesting valuable IP.

Dr. Tajeshwar Singh is qualified European Patent Attorney with deep interest in technologies in general — from vintage to state-of-the-art. He also has hands-on experience with mechanical systems and tools.

He created valuable IP and handled mission-critical commercial projects in his previous roles. He is passionate about digitalization and patents for digital technologies.