Meta’s frenemies—executing on innovation and IP when your social graph is complicated

Meta just released its new Quest 3 headset in October following its announcement in June 2023.

Oculus VR was acquired in the aftermath for USD 2B on 25 March 2014. Oculus was just two years old at the time, founded by Palmer Luckey in 2012 when he himself was all of 20 years old—a remarkable story in itself.

So what the heck has Meta been doing this last decade, now that the company enters its third act? How does the Meta story resolve?

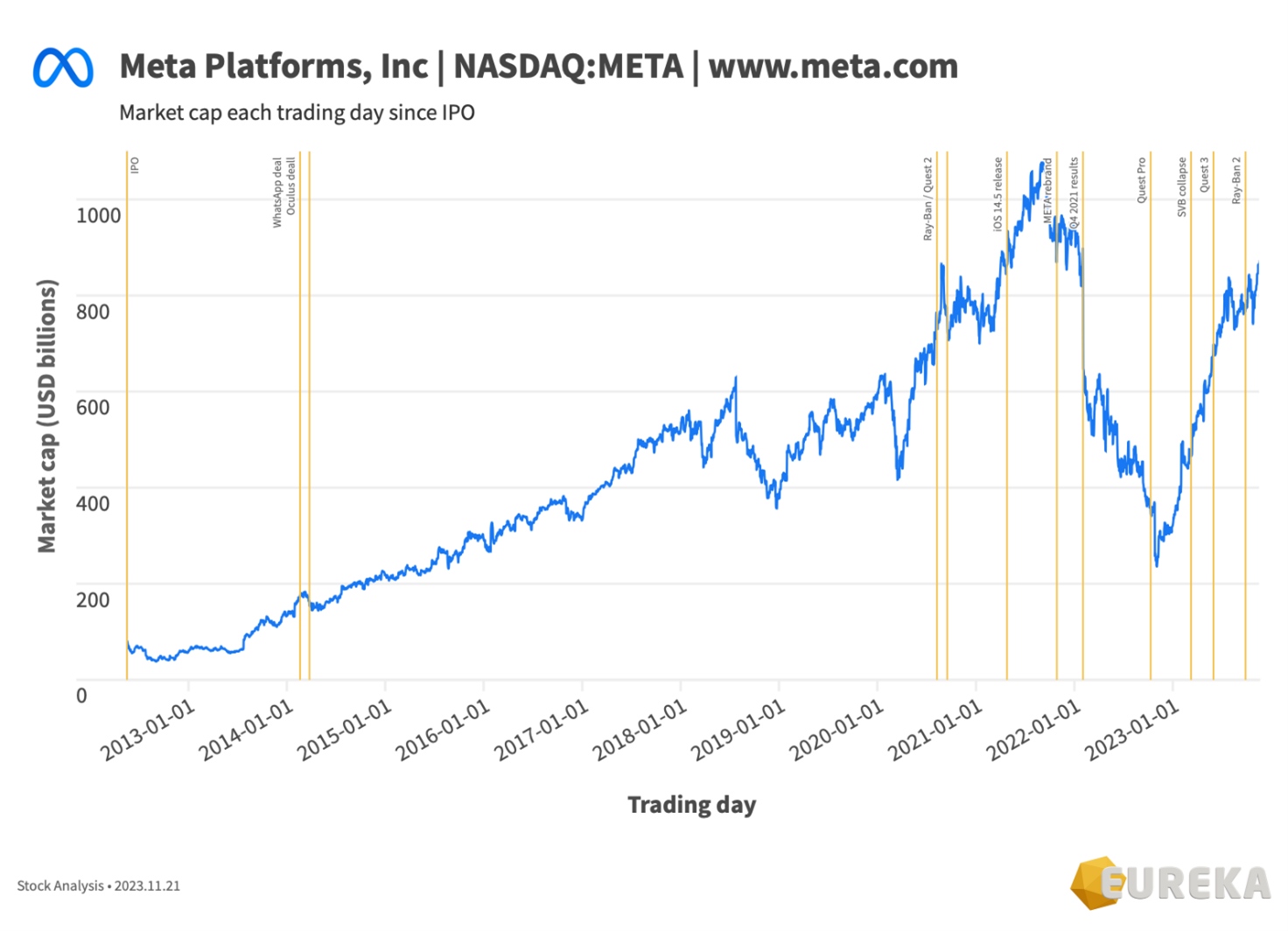

Figure 1

The Meta story started life as a book so to speak, or perhaps a screenplay more accurately.

Unlisted Facebook set the exposition phase of Meta, with listing on 18 May 2012 marking a conflict point between its hacker era and publicly listed responsibility.

The META stock price—as a pulse of its dramatic fortunes—has certainly tracked successive phases of the classical narrative arc—namely rising action, climax and falling action. And since the low of October 2022 we’re a year into the resolution phase.

Figure 1 above tracks Meta’s market capitalization—annotated with the milestones that are touched upon later.

Meta’s patenting programme since listing fuelled the company from a generously priced USD 100B initial public offering (IPO) through a 10x growth trajectory that broke USD 1T at the climax before the fall.

Wind back a decade, back to 2012, as now, not everybody associates software with IP—and even less so social media.

Even Facebook.

They didn’t really patent anything much from inception in 2004 to listing in 2012.

With the public listing in the works, Facebook panic bought a LOT of patents, and also started generating their own.

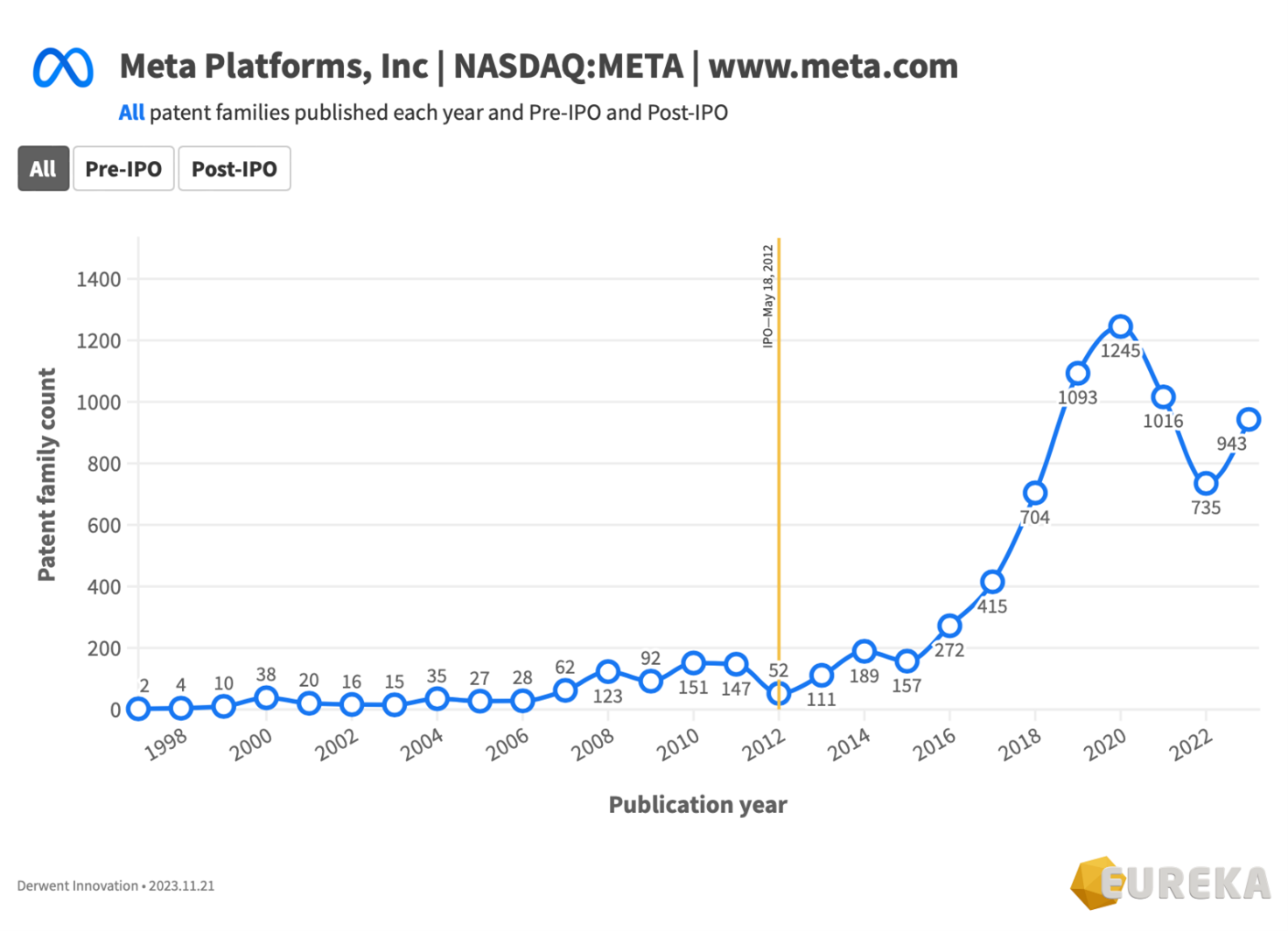

Figure 2

Figure 2 above charts the Meta patent publication numbers by year, with the IPO serving as waypoint.

Didn’t Facebook launch in 2004? Yes, don’t be fooled by the pre-IPO numbers—the patents were bought not built in deals from around 2011 on that marked the end of the hacker era Facebook.

The definitive close of that hacker era was the ringing of the bell on the NASDAQ trading floor that launched public trading of Class A shares. The original stock ticker was FB.

(Meta like Alphabet companies has a dual class structure, the upshoot of which is Zuck retains the controlling interest via Class B shares as well as a substantial Class A holding and so is a pivotal character beyond being CEO).

At the time I was intrigued by the Facebook acquisition spree and so in 2014 was I inspired to pull together a piece (made a Facebook post?) looking at the IP situation for Facebook before and after IPO.

You can review Facebook likes IP as originally posted via Lexology (which even lets you like it!) and consider this update as one of those belated, bloated comments in reply to a long forgotten original post.

As was well covered in business media at the time, the scope and scale of the patent acquisitions was impressive.

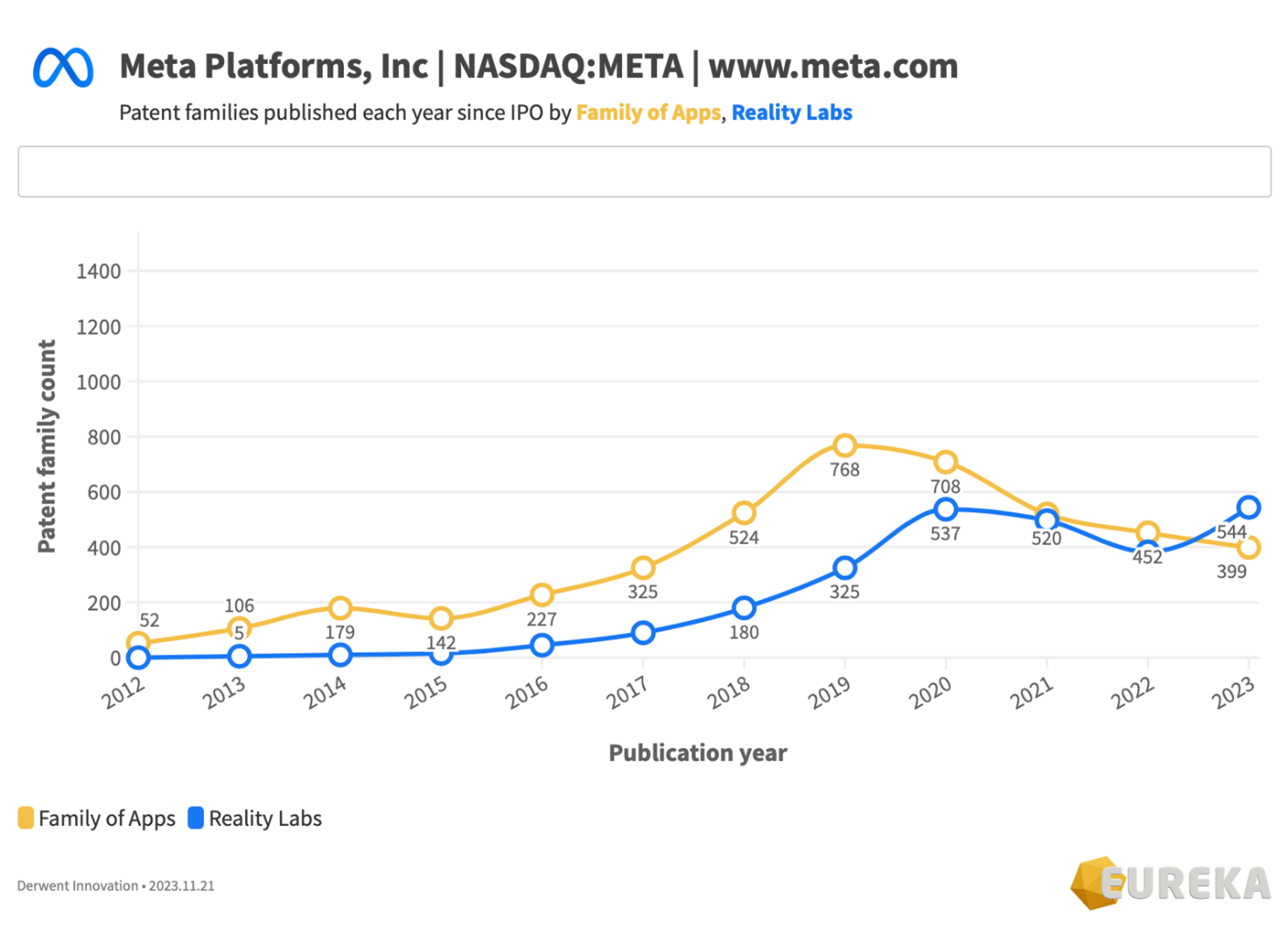

Figure 3

Extraordinarily, for a good half decade after the IPO every patent published by Facebook manifested another USD 1B in market cap—as if by magic. This can be seen in Figure 3 above.

Then the pattern broke in 2018. That’s not to suggest the tail was wagging the dog (if only!) but the data does surface this correlation over that period.

Would you not accrete as many patents as you could while that kept happening?

So that’s what Facebook did, and retained very strong patent publication numbers for 2018–2020 despite lagging market cap.

Figure 4

Incidentally, 2018 was when headset patent publications were in the ascendency, and only overlook social media patent publications this year, 2023. This can be seen in Figure 4 above.

As well as recapping the past IP strategy from inception to lPO, we’ll dissect from IPO through the following decade just gone and set the stage for what resolutions are possible for Meta in its coming metaverse era ahead.

The metrics of success and failure are in no small part governed by the innovation strategy and commercial strategy, with IP strategy and execution in a supporting role. The IP data does however provide an easy entry point to try to make sense of what’s happening.

Essentially, can Meta win coming from behind, without possessing advantages possessed by its strongest competitors? And all in the face of AI terraforming the logistics of content generation and other aspects of the digital landscape in ways that are elusive to anticipate over a ten year horizon?

Before dissecting the past and speculating on the future—it helps to cover how things have gone for Meta from the 2012 IPO.

Backgrounder

Famously Facebook pulled a hackathon all nigher on the eve of the IPO so everybody could be around and pumped when Zuck rang the opening bell at start of public business on Nasdaq. And that bell rang loud and clear to the tune of an incoming USD 16B at a valuation just north of USD 100B.

More recently, for a very brief period Facebook broke through the USD 1T market cap ceiling in August 2021. After renaming itself Meta in October 2021, the market cap promptly collapsed to the point where this time last year it was close to three-quarters off its peak just weeks before.

A lot of blame for this can be laid at the feet of Apple’s Tim Cook. Zuck and Tim Cook have a long standing feud back to 2014 at least, and have been trading public barbs over the years.

Apple rolled out iOS 14.5 in April 2021, which featured the ‘Ask App Not to Track’. The alternative is ‘Allow’, which is probably not the majority choice.

Apple was yet again leaning into privacy and security branding, a strong and impregnable differentiator over Android, and one reason why consumers pay a bit more for Apple.

Facebook was rumoured at the time to be preparing antitrust litigation against Apple, supposedly citing restrictions on app developers via the Apple App Store.

Apple responded by taking some free money from Facebook. Once iOS14.5 got on iPhones, Apple’s pro-consumer move hurt Facebook stock and nobody knew quite how damaging it might be. And worse, Facebook had no possible strategic countermove, and just had to take it.

Facebook investors were also underwhelmed by the Meta rebrand that shortly followed—the metaverse narrative didn’t match what was public and visible at the time.

The Oculus VR deal was long ago and the recent Quest 2 and Ray-Ban products hadn’t achieved mainstream traction.

While the rebrand was presumably a signal of Meta’s rising metaverse ambitions, for investors it only served to expose, one, low confidence in the status quo (advertiser revenue felt under threat) and, two, how little of Meta’s fortune appeared under Meta’s control.

Let’s not forget tech stocks were down anyway on a tough 2022. Nobody agrees what really caused this—a mixture of rising interest rates, an inflationary environment, poor revenues, cybersecurity hysteria, supply chain challenges and so on. Lots of bad vibes all round.

Fittingly, this difficult period was bookended by the spectacular collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in March 2023, with a lot of tech companies having all their cash there.

Meta’s stock has now bounced back to 2021 levels and is again shooting towards the magic USD 1T mark so go figure.

Meta’s different IP eras

Let’s rehash the first two of Meta’s IP eras from Facebook Likes IP, and also bolt on the next era, the metaverse IP era.

Act I: Hacker era IP strategy

Let’s call this strategy ‘Move fast and break things. Unless you are breaking stuff you are not moving fast enough.’

The nuts and bolts—

- File some patents, and opportunistically buy any patents if they threaten to compromise immediate operations

- Employ key engineers at very high salaries and benefits to safeguard trade secrets

- Own data generated by the platform at any cost via cunning use of copyright

Act II: Listed era IP strategy

Let’s call this strategy ‘We‘re at the stage now where we can take a step back and think about the next big things that we want to do.’

The nuts and bolts—

- Acquire as many patents as can be practically brought for defensive and assertive purposes

- Lay the foundation for complete IP domination of the greater social networking space

- Anticipate and contingency plan any aggressive posturing from third parties

Act III: Metaverse era IP strategy

Let’s call this strategy ‘This is a perverse thing, personally, but I would rather be in the cycle where people are underestimating us. It gives us latitude to go out and make big bets that excite and amaze people.’

The nuts and bolts—

- Scale back the patent programme in terms of numbers

- Shift IP focus from social media to headsets

- Get more strategic for the win

Critical review

I sketched out the summary of the metaverse era IP strategy points above based on running the numbers to see how things had gone for Meta.

Though not before reviewing wonderful coverage from Angela Morris dated 23 August 2023 that highlights Meta’s acquisitions and licensing activities are busier than ever. This is aptly entitled Meet Meta’s patent team, in which diversity strengthens strategy, acquisitions and licensing.

Alas, this content is paywalled at IAM Media so may not be available for some. The most interesting aspect however for me was some of the on-point discussion arising from wide ranging interviews with Jerimiah Chan, head of patents, open source and licensing at Meta.

With a mixture of satisfaction and relief, points from Acts II and III look to be vindicated both in 2013 and in 2023. I’ve set out the two most relevant passages below.

“We want to be good stewards of the significant budget we have for building the patent portfolio and ultimately make sure that it’s the right portfolio for the company,” explains Chan. “In a nutshell, how we are re-thinking the patent strategy is: do not over-build. We’ve had a proliferation of patents in the US because most companies simply file too many of them. You have to make sure to right-size the portfolio, using lots of relevant data to understand the competitive landscape in conjunction with the business roadmaps. We ask: ‘Where is the business going and how do we make sure we anticipate these areas in order to facilitate Meta’s freedom to innovate?”

“We have had a very active patent buying programme, and that programme relies heavily on data analytics. We are looking at data all the time to understand different patent landscapes. What are the entities that own the patents and which operating companies sold them in the first place? Who are the patent owners who own really strong patents in a particular technology area – those fundamental innovations that many other patents cite to, and that all those other patented technologies rely on and are built on,” Chan reveals.

So far, so good. But what does execution across the next decade look like?

The lofty ambitions of metaverse era IP strategy rests upon some big assumptions—

- Reality Labs patent portfolio will create a meaningful IP position for headsets/smart glasses

- A reliable pipeline of compelling IP is available for ‘excite and amaze’ experiences

- Meta can survive and thrive in the face of gross uncertainties, such as existential patent wars, a flood of AI content IP from rivals, an open format metaverse and more.

This is to say that the IP strategy is hostage to the innovation strategy and commercial strategy.

Let’s hope Act III doesn’t conclude with ultimate action movie trope of Jerimiah tied to a chair with a gun to his head—with the baddies asking him to deliver things outside his powers!

How deep a risk is Meta’s big bet?

So far Meta’s metaverse IP strategy has been all ‘big bet’ and no ‘excite and amaze’.

Why such a big bet?

Meta made its fortune on a premise that worked followed by unrelenting incremental innovation at every step. A lot of acquisitions de-risked its operations every step of the way. Now it’s slipping out of character and taking on the biggest risk it can, and headfirst.

One, Meta is launching into hardware products. Also, original content creation is an area where Meta has no natural strength, but where it is likely to need to demonstrate competence. Meta’s business has conventionally leveraged user-generated content.

Also, Meta is chasing a different market to that associated with the existing market for its Family of Apps. Family of Apps is for the familiar mass market demographic.

The Reality Labs caters to a different market—XR headsets and smart glasses are far from mainstream and for now feature a cast of early adopters, gamers, and the folks who were chasing Pokémon through the streets in 2016.

The Ansoff Matrix, also known as the Product/Market Expansion Grid, is a framework for presenting strategies for diversification and their associated risk profiles. Igor Ansoff originated the Ansoff Matrix, which was first published in the Harvard Business Review in 1957 in an article entitled Strategies for Diversification.

The Matrix is presented in the familiar 2×2 quadrant graph format, with each of the alternative axes depicting products or services differentiated as existing vs new. The status quo is serving the current market with the current product.

The idea is that each time you move into a new quadrant (horizontally or vertically) by moving product or market, risk increases. Needless to say, Meta is changing the product it offers and the market it serves at the same time, which is a diagonal move, and carries the highest risk profile.

So at the least it’s a very bold move, and all the more so as even lateral innovation to other social media platforms were as the result of acquisition (Instagram and WhatsApp).

But what’s the upside?

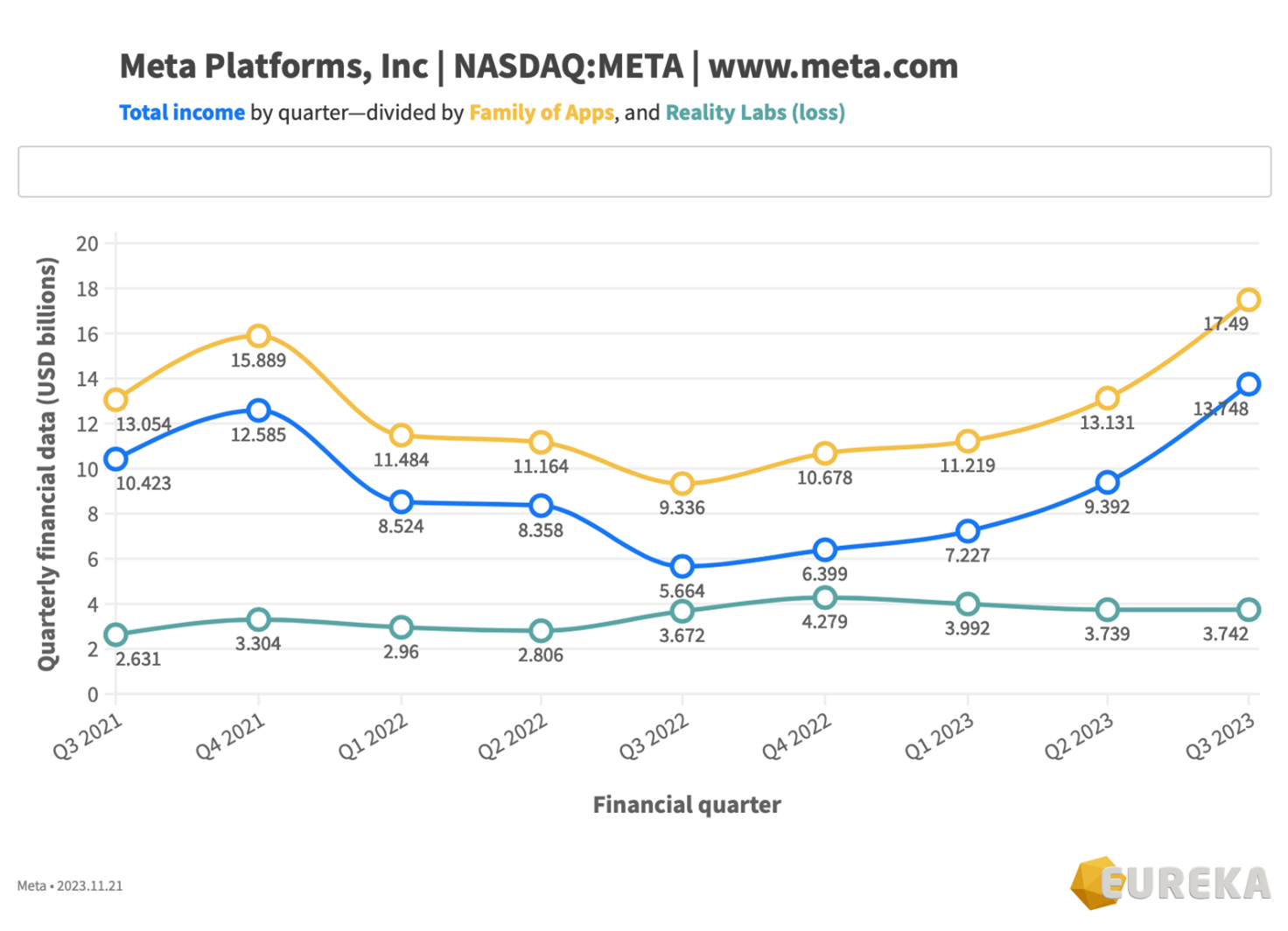

The Reality Labs numbers are not encouraging thus far, seen in Figure 5 below. Reality Labs is a loss-making machine. Revenues from Family of Apps are routinely USD 30B per quarter, whereas revenues from Reality Labs are yet to get near USD 1B per quarter. Instead, multibillion losses. This would only be possible with the generally strong ongoing cashflow from Family of Apps. Few companies have the ability or will to absorb such losses for so long.

Figure 5

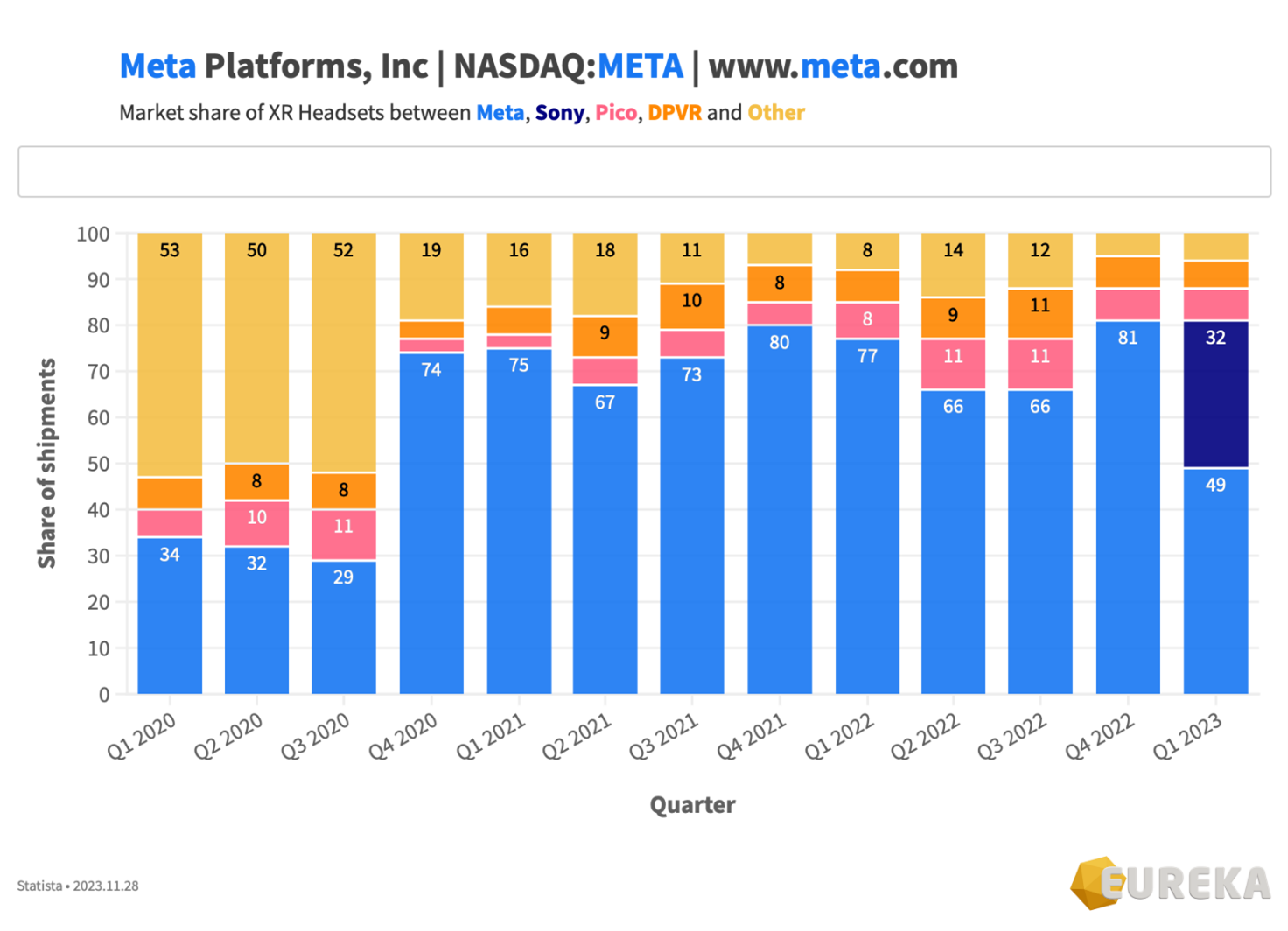

Figure 6

So with such a deep commitment, they’re dominating headsets right? Yes and no…

Figure 6 above shows numbers that are now two quarters behind but still has some use. Meta has done a lot to bring headsets to the masses from late 2020 thanks to the loss making release of Quest 2. This was enough to entice some people to try VR at an easy price point. Then Sony comes in with PlayStation VR2 and eats Meta’s early lead, without much difficulty it seems.

One can only assume that Sony made ground through 2023, which Meta offsets with the new Quest 3.

A juicy piece of palace intrigue (actually public knowledge) is that Andrew Bosworth, CTO of Meta kept himself busy in 2023 selling off USD 9M of META, the most recent movement being the best part of USD 3M on 15 November 2023.

Andrew has been CTO since January 2022. So it’s tempting to speculate whether he just has one of those difficult personal lives. Perhaps, just perhaps, he’s not super bullish about what he’s seeing at work. And this is despite the stock being on a vertical recovery after a disastrous 2022.

Andrew’s public statements have all been about the fantastic value creation Meta’s making for its longer term headset future, all as Reality Labs reliably loses billions each quarter. Well, what is he supposed to say?

The most obvious point here is that people will go where the fun is and the PlayStation and Xbox console makers Sony and Microsoft do have that hard earned hardware expertise along with deep knowledge and familiarity with what experiences land with their sizable audience.

What happens from here for Meta?

Meta is certainly a committed entrant with delivery. They were not placed to capture handsets, but they have a shot at headsets.

Looking ahead, the problem is what does success from here even look like? It’s difficult to envision in such a dynamic environment.

Meta’s AR/VR hardware roadmap was covered by The Verge earlier this year (in May 2023). Interesting read—but so many assumptions.

Quest 2 and 3 have been well received. As things stand, though, Meta is assembling Android tablets you strap on your head.

Meta abandoned work on its own Oculus Quest OS for Quest 3. It’s gone with Android Open Source Project (AOSP) for now at least, and like a bunch of other headsets uses Qualcomm’s Snapdragon XR2 Platform.

As an example, the AOSP/Snapdragon XR2 stack is used by not just Meta, but also the Pico range (acquired by ByteDance in 2021). Obviously, this makes everything quick and easy to assemble with minimal barriers to entry, but it also means that ughhh, everything is quick and easy to assemble with minimal barriers to entry.

And there a bunch of others using Snapdragon, and a bunch of others using AOSP.

So you already have the dynamic where Meta and some of its competitors are stuck reconfiguring their products as next generation of Qualcomm hardware is announced and released, which makes it hard to build transformative products over the longer term.

As for Pico, reports are ByteDance is scaling back the Pico offering as of November 2023—citing poor global demand.

Apple—for contrast—is using its own M2 and R1 chipsets and own visionOS, which means seamless integration with macOS, iOS, iPadOS and full command of the product roadmap. Speaking of which, carOS? The Apple trajectory is a far easier journey for any supporting IP strategy.

Apple has confirmed that nearly all iPhone and iPad apps will be available on Vision Pro from the App Store as it becomes more available in 2024.

Meta has already suffered the indignity confirming that they asked Google to bring Google Play to Quest 3—and Google politely declined. This came out in an Instagram AMA session on 7 November with Meta CTA Andrew Bosworth, the abovementioned who’s been selling his META stock, most recently 15 November 2023. What drama!

A lot remains uncovered here, such as the glaring question of why Facebook never sought to develop an innovative video-first platform as part of its Family of Apps. This seemed for the taking given the proven success of Instagram and YouTube. Antitrust concerns may certainly have played. Meta is still in ongoing ligation with the Federal Trade Commission about Meta accumulating monopoly power via anti-competitive mergers centring on the Instagram and WhatsApp acquisitions.

Also, zooming right out, handset to headset is just a stepping stone to what’s next. The ideal headset is no headset. It’s already the biggest complaint people have. The next phase after the wearable metaverse is the everywhere metaverse of pervasive compute that’s embedded all around you. Think the ceiling projector in Blade Runner 2049.

So for now while Meta has already built a large and growing metaverse/headset patent portfolio, how effective that portfolio is in serving and supporting Meta’s commercial ambitions in the headset metaverse remains an open question.

Zuck is on record saying a core reason for the Oculus buy was to reduce his company’s dependency on the platform holders—Apple and Google—in the metaverse era of personal computing.

Coming into 2024, Meta is still faced with the same complicated friendships of 2014.

About the blogpost author:

David is an Australian-based patent attorney operating in digital innovation. Currently, he operates Eureka—a patent boutique in Melbourne, Australia that focuses on early stage technology companies in fintech, artificial intelligence, medical devices and autonomous vehicles amongst other fields. David has predominantly worked in private patent practice with a main focus and expertise relating to computer-implemented inventions, for a range of client types from entrepreneurs to multinationals. After university studies he completed a project in biomedical engineering deciphering ECG ‘noise’ to predict imminent onset cardiac arrhythmia episodes signalled via the degradation of markers for health variability using fractal analysis. David is at present participating as a committee member for The Churchill Club, an organisation that holds regular panel events of themed domain experts discussing major trends affecting particular emerging technologies. David also maintains an interest in IP valuation, and holds post-graduate qualifications in Applied Finance and Investment, as well as Electrical and Computer Systems Engineering and Science degrees from Monash University in Melbourne.

David is an Australian-based patent attorney operating in digital innovation. Currently, he operates Eureka—a patent boutique in Melbourne, Australia that focuses on early stage technology companies in fintech, artificial intelligence, medical devices and autonomous vehicles amongst other fields. David has predominantly worked in private patent practice with a main focus and expertise relating to computer-implemented inventions, for a range of client types from entrepreneurs to multinationals. After university studies he completed a project in biomedical engineering deciphering ECG ‘noise’ to predict imminent onset cardiac arrhythmia episodes signalled via the degradation of markers for health variability using fractal analysis. David is at present participating as a committee member for The Churchill Club, an organisation that holds regular panel events of themed domain experts discussing major trends affecting particular emerging technologies. David also maintains an interest in IP valuation, and holds post-graduate qualifications in Applied Finance and Investment, as well as Electrical and Computer Systems Engineering and Science degrees from Monash University in Melbourne.