Economics of Streaming & the Rise of the Music Artists’ Rights and Compensation

This article was originally published by the International In-House Counsel Journal at this link.

ABSTRACT

As the big era of buying CDs and vinyl records has mostly passed, music streaming continues to hit the music industry by storm. It is a market estimated at $153 Billion [1] with no signs of saturation. Nearly 2 billion music discoveries happen on Spotify every day. Headlines continue to sweep across the news media and this month the FT reports [2] “Universal music strikes deal to reshape streaming economics”. Broad industry alignment is required to re-monetise the music making lifecycle to benefit artists, limit non-artist noise, and ensure a better-quality user experience. This is particularly challenging where current fragmented and inconsistent regulations across different jurisdictions are struggling to keep pace with technology developments.

In a generation where new music is so sought after, it is important that the rights of the artists are not ‘’stepped upon’’. Underneath the simple world of radio hit music, popstars, and chart dominating artists, lies a complex world of compensation, business models, copyright, licensing, and online piracy. The music industry will keep growing through many platforms on social media, such as Tik Tok, thus, elevating these problems as more artists are entering the industry.

This overall impact has not been financially beneficial for all parties involved in the music ecosystem, including the record and streaming companies, and any other intermediaries in the supply chain. Artists, especially of today’s generation and new artists, have been most affected by the lack of adequate compensation by streaming platforms, such as Spotify, Apple Music, Deezer, and Amazon Music. Business models need to support artists at all stages of their careers whether they have 1000 fans or 100 thousand or 100 million. For too long artists have not been equitably compensated and economic review of their business models is required to uplift compensation due for the artists.

The trouble of fair compensation to artists and intermediaries has been scaled by illegal downloading and music piracy, where individuals can promote music illegally on their own site. This was first promoted on the site Napster which advocated for wholesale infringement and consumers were easily attracted to this as it was highly unlikely at that time that they could get caught. The Napster site was set to have 70 million listeners which was very large for a company in the early 2000’s at the start of the technology revolution [3]. Lost revenues due to music piracy means less royalties to give to artists.

Artificial Intelligence has completed Beethoven’s unfinished 10th Symphony and wholesale copying of authors’ works to train large language AI models is another hot topic. The lawsuits have started such as against Open AI (company behind AI tool ChatGPT) claiming breach of copyright laws by training its model on materials without permission. Recent UK governmental committee intervention has identified IP protection as vital to much of the creative industries, and the impact upon it from the rise of AI technologies, particularly the text and data mining (“TDM”), of existing materials used by generative AI models to learn and develop content. AI has diluted the rights of music holders especially when considering the TDM exception was broadened by governmental intervention early this year, to any purpose, but the government retuned to the previous narrow definition in the summer after right holders were raged. A balanced approach is required to ensure protection and remuneration for copyright holders, whilst providing reasonable access and use of works for others such as AI developers.

This paper explores some current issues addressing the concerns of the music artists in the streaming world both from the perspective of rights and fair compensation. Should streaming platforms’ business model be revised to come to a fair consensus? How are artists paid based on the split between their record labels and the streaming platform? Which business models are appropriate for streaming platforms, the Pro-Rata or the User-Centric model? Should the different models be specific to consumer preferences and different age groups? How to fix online piracy? Should the artist be independent of the companies supposedly representing their interests? What are the next steps in AI music?

INTRODUCTION

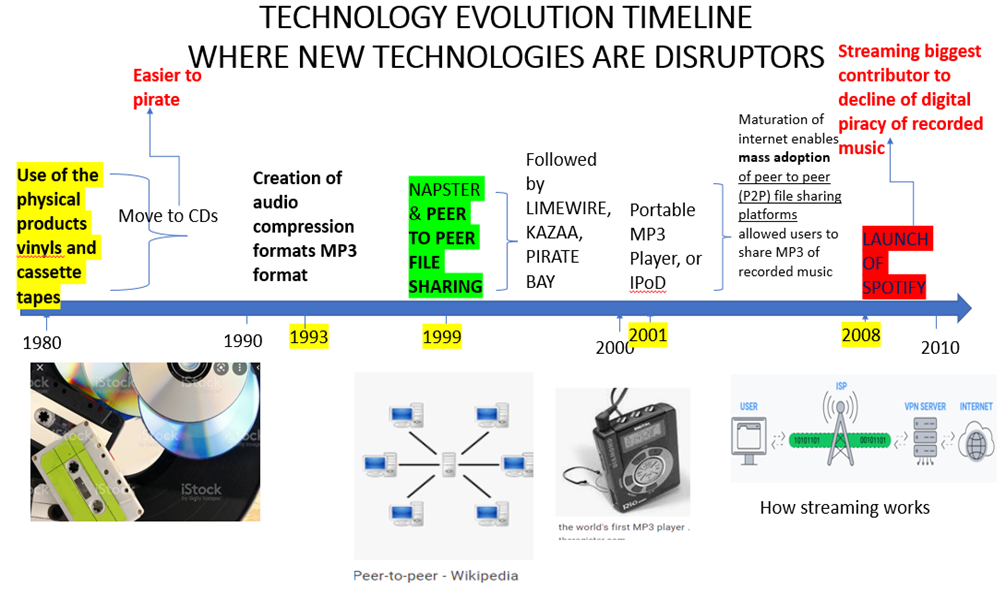

The technology evolution timeline is shown in Figure 1 below. In the early 2000’s, the early digital technology disruptors, such as Napster, LimeWire, the Pirate Bay, introduced the concept of downloading. Downloading is where you wait for the user to obtain the entire file before you can listen to the song and the user allegedly copies the music file. Napster file shared using peer-to-peer networks where that file was placed on the internet giving access to users to illegally download it [3].

Spotify was first set up in 2006 [4] and created a monopoly in the music industry, bigger than the dominant record labels, introducing streaming. Streaming is where you can start listening before the entire file has been transmitted and temporary files are transferred to the user whilst the audio is being played. Unlike Napster, Spotify initially recognised the rights of artists and the need to have the right to use permissions or licensing. Also recognised was the issue of illegal distribution of the works of artists.

The Music Ecosystem & the dominant actor in the music lifecycle

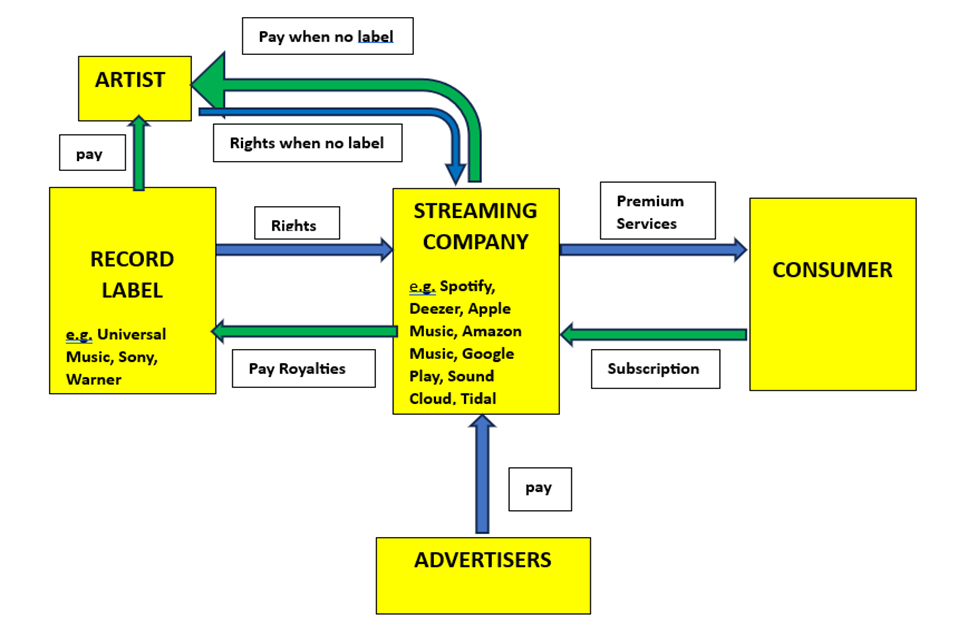

There are many actors (see Figure 2 below, highlighted in yellow) involved in the music lifecycle or music ecosystem. Each actor (from consumers or users, artists, producers, publishers, and to all those intermediary parties) contribute to creating or producing the music. Other actors include various enforcers, such as courts, governments, or internet service providers (“ISPs”), or collection agencies, who can intervene and enforce rights and collect royalties.

Traditionally, there were a greater number of actors involved in the creative process of making music: artists, music studios, producers, engineers, designers, publishers, marketing, or promotional divisions. The record labels, such as Universal, Sony and Warner, were relied upon by the artists to take care of all those activities such as music production, branding, manufacture, marketing, promotion, and distribution.

In the new digital age, all actors are redefining themselves in roles and contributions in the music making lifecycle. Records labels must now share their dominance with the streaming actors, such as Napster, Spotify, Apple Music, Google Play, Deezer, Tidal, Sound Cloud. Today, the battle for dominance continues, and moreover, so does who should therefore have the highest level of compensation. There is obvious tension between how much money should be kept by the streaming companies, record labels, and artists based on their level of dominance. Arguably Spotify’s monopoly power in the online music industry may now be potentially worse than the previous domination of the big record labels.

The problem of online piracy diminishing compensation due to artists

Napster introduced the new concept of online piracy, and this was the reason why Napster was closed for illegal distribution of file sharing without permission from artists. Artists have become more exposed to online piracy, music leaking or stream ripping, and the music industry has lost billions of dollars because of it. Spotify highlighted the problem of online piracy and the need for licensing to obtain permission from artists to use the works of artists and their lyrics.

Napster allowed users to trade copyrighted MP3 sound files, or file share, between each other, making it easier for participants to download copies of songs. There were several lawsuits filed against Napster which alerted artists to be more cautious of copyright laws. For example, ABC news reported [3] that the band Metallica sued Napster because over 300,000 people had pirated their song’s online, forcing Napster to block 30,000 users. Metallica believed that Napster was in the wrong because they were not ‘sharing’ their music but instead duplicating (or copying) their work without their permission, which was not fair use.

RE-MONETISING THE ONLINE MUSIC INDUSTRY FOR PROMOTING ARTISTS’ UPLIFTED INCOMES

Napster technology was popular because consumers wanted to listen to music using sound files and not use the physical product and importantly not pay for rights to copyright owners in disregard of copyright laws. Spotify recognised rights and introduced subscriptions for consumers and royalties for artists holding those rights. However, artists have publicly spoken about the poor royalties, including Taylor Swift who compared Spotify to an experiment [4].

Both online piracy and Spotify’s cuts in renumeration for artists’ works has not only affected the artists, but also the people surrounding them. This means there are lost revenues for artists, engineers, cover designers, producers. Too many players in the music ecosystem want to own rights and have the largest percentage of compensation. However, what do these parties contribute to the artistic creation and overall music production process such that their contribution justifies more compensation?

- Artists assert the value of their song and want to have rights to own their music to prevent both exploitation and infringement and are the largest contributor to creativity.

- Streaming companies argue: (i) they have invested heavily in building software, platforms, and services; (ii) they are taking on the roles of marketing and branding; and (iii) they have revolutionised the amount of success artists are able to reach due to them being the main method in the consumption of music and are now seen as a promotional tool.

- Record labels want to own rights being the largest face in the music industry argue that they are still the dominate contributor, spending the most money bringing the song to market.

Transparency, clarity, and balance is required amongst the actors for the largest percentage of compensation due.

Spotify Business Model

Spotify has become one of the biggest streaming service providers, as reported Q1 2023, having 551 million active users worldwide (220 million premium),, over 100 million songs to choose from, and 4 billion playlists across all genres [5, 30]. Spotify’s popular fee-based subscription model and consumers’ non-paying alternative advertisement-driven; both options are made to aid the artists’ compensation. To consumers with non-paying preferences (outside premium services), advertisers can pay the streaming services to help sell their product or service. The advertising revenue gained can be used to pay more to the artists.

Figure 2 shows a highly simplified model with various actors involved in transferring rights and actors involved in receiving payments.

Spotify was reported to pay £0.002 and £0.0038 per stream to the right’s holders to maximise their own revenue [7]. The streaming services keep approximately 30% of the money collected whilst record labels keep about 55% of artists’ revenues, leaving the artists’ compensation at about 13% of the total revenue generated from their works [13]. In comparison Apple Music, pays twice the amount per stream (£0.0059 per stream) and Amazon pays triple the amount [8].

Pro-Rata model versus User-Centric model

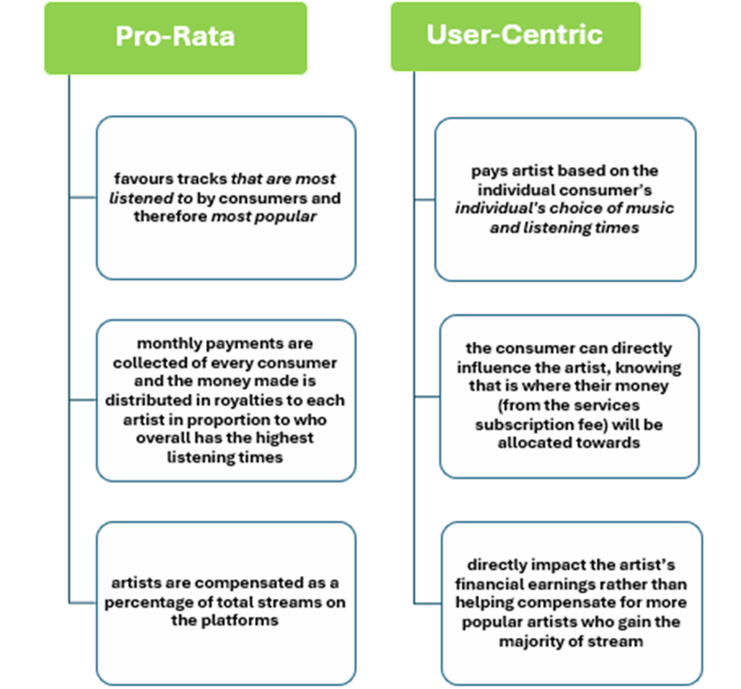

Two business models are generally considered when compensating the artist: the User-Centric model; or the Pro-Rata model [9].

The source [9] believes that in the pro-rata model the artist is not fairly compensated. It is argued that artists with more popular tracks should be favoured more than an individual who is lesser known in terms of revenue generated. Artists are compensated as a percentage of total streams on the platforms, rather than their own share. It may mean the money paid by individuals on a subscription-fee basis may not go towards artists they listen to.

For the pro-rata model, listeners’ monthly subscription fees are pooled together into one royalty pot that is divided among copyright holders based on their share of listening, for example, Spotify pay about $0.005 per stream or $5 for 1,000 streams regardless of whether streaming originates from an artist or a bot [7]. Royalties are paid the same regardless of who created the song or whether the song is listened to passively via an algorithm or actively by searching for it. If someone or something listens to it for more than 30 seconds, then the stream counts.

Spotify’s Response, the Universal deal & broad industry alignment required to the User-Centric Model as a step forward for the music industry

In response to the poor compensation claims by artists, Spotify introduced a ‘’tip jar’’ [10] where users can send money directly to the artist on the platform in hard hit covid times. Arguably the tip jar is a ‘’slap in the face’’ for artists because Spotify was primarily created to help artists who have lost out on money from online piracy. The source [10] gives evidence to show Spotify has not helped their situation and money is still a problem.

Also in response, Spotify released a campaign called Loud and Clear. Spotify explained that their artists are not paid per stream, but instead in proportion to how popular the song is in each country. The Loud and Clear campaign argued that they pay two-thirds of its revenue to rights holders [11]. Further, they argued the royalties record labels give to an artist have nothing to do with Spotify but are instead involved with the contract between the artist and the label. This removes the problem away from Spotify and pushes it to the copyright holders.

The Loud and Clear campaign demonstrated that Spotify would be happy to switch to a User-Centric model but argued they would need broad industry alignment for this change to be possible. This could still be solved because Spotify works in partnership with all the major labels at hand, so there is less stopping them from implementing this change.

Universal Music and Deezer [2, 28] are proposing a deal akin to the User-Centric model, and an Artist-Centric Music Streaming Model, to address the flood of uploads with no meaningful engagement, including non-artist noise content.

Here artists’ compensation could be uplifted to 10% based on the following [28]:

- for professional artists, i.e., those that generate 1000 listens a month will be given double weight of streams; and

- if the listener activity sells out a song the weight of those streams will double again.

- Deezer is planning to replace non-artist noise content with its own content in the functional music space, and this will not be included in the royalty pool.

For example, they report [2] if a consumer searches “TaylorSwift” on the Deezer app and listens to one of her songs, then it will be counted as four streams for royalty payments.

In the same FT article [2], Deezer reportedly would pay two thirds of every dollar they collect to Universal and royalties for professional artists would be uplifted by 10% but only for a threshold of 1000 streams, only for human artists, and no royalties for “noise” created by bots or otherwise presumably non-professional artists.

Whilst Spotify, Universal, and Deezer have, at least, reportedly indicated a shift to the User-Centric model, broad industry alignment is required. There are indications that times are improving with Spotify reportedly having paid $8 billion to artists in 2022 [30] which is more than any other music streaming service.

User-Centric model favoured for different genres of music, such as classical or hip hop, but what about new unknown artists or non-professional artists

Moving to the User-Centric model would benefit those professional artists based on those consumers’ individual choice of music and preferred listening:

- streaming revenues for classical music would go up by an estimated 24%; [12] and

- rap and hip-hop would remain the most paid streaming genre in the music industry [12].

Hence, it could be argued that this fairer share of revenue to less-listened genres could still be at benefit for the rap and hip-hop industry.

However, is the proposed User-Centric model excluding the upcoming new unknown artists who do not fall into the category of “professional” artists? This exclusion would be impactful to smaller artists who have the most reliance on keeping their own revenue for production purposes so they can make more music. Record labels/streaming companies also need to favour smaller new artists in line with consumer preferences to new talent.

Rise of the independent artists without record labels

In recent years, some artists have decided to part ways with their record label. Becoming independent means that artists can create their own revenue streams and be free of the overpowering record labels [14]. Here the individual artist can make more than the meagre average 13% of the total revenue generated from their work [13] where record labels receive most of the money made from streaming services.

Artists argue they no longer need a major record label, such as for Beyonce, where independency has enabled her to control the selling price, to know how many albums she sells and to control when they sell, to maximise her own financial gain.

Record labels need to reconsider their one-sided contracts in licensing and publishing deals favouring themselves without artists permission and propose new copyright laws that are in correlation with not only their economic interests.

On the other hand, independent artists having complete control over their work will take lots of time for the artist to manage everything, when artists take on the many multifaceted roles of the record companies and/or streaming companies. The artist may have to implement a marketing strategy for their music, and they will have to understand the trends of the music industry by themselves. Also, this includes the costs involved in touring, potential merchandise for fans and music videos. The independent artist may not have the same network of connections and industry contacts as a record label may have, this may be highly damaging to a smaller artist who could lose many sales [14].

A balance is required between the requirements of the actors in fair apportionment.

New business models for fair compensation

Whilst Napster created free downloading for all users, tech disruptors introduced its new online streaming which required people to pay subscription fees for premium services. Artists assert that tech disruptors or record labels take an unfair cut of the money owed to artists and artists receiving less royalties. This has forced tech disruptors/record labels to build new business and legal models to benefit the artist for better fair compensation. Post-Napster the activities conducted by the various players in the music ecosystem have changed such that we can question whether the record labels or streaming companies need to play such a dominant role.

Artists without record labels and those creating their own streaming services are also on the rise again. Artist Jay-Z responded to Spotify’s poor compensation by creating his own streaming service called Tilda, in which Beyonce representatively placed most of her music alongside him [4].

Artists such as Beyonce, Ed Sheeran and Coldplay have decided to offer CD’s and digital downloads before placing their music on streaming platforms such as Spotify [6]. They argue that streaming services have become ineffective in persuading people to hand over their money. For example, only 1% of potential subscribers (being active internet users) pay for the fee-based service on Spotify [6].

There are also new players with new business models emerging. Stability AI propose open and permissive models to help transparency, such as their public release of Stable Diffusion [26], where third party companies can build their own models. There is another open-source language model such as Llama2 from Meta AI [27]. Further, Hipgnosis who have impressively invested £3 billion in acquiring the IP rights to the most important music to over 150 most successful song catalogues, whose licensing business model is to collect royalties on behalf of artists [24]. Last week there was the Litmus Music deal with Katy Perry, reportedly worth around $225 million, marks this year’s biggest catalogue deal with a single artist [25].

INCREASING ARTISTS’ COMPENSATION BY RESOLVING ONLINE PIRACY

Online piracy, music leaking, or stream ripping can be fixed in several ways, including new delivery models or enforcement systems. The courts, ISPs, collecting societies, or the government can do more. Courts could enforce the copyright ownership of an artist’s work, but this solution is very expensive. ISPs, such as the telecom giants, can do more to block access to websites hosting infringed material. Agencies, such as the International Federation of Phonographic Industry (“IFPI”), Recording Industry Association of America (“RIAA”), British Phonographic Industry (“BPI”), can all further step up to represent artists and help protect royalties.

Also proposed, a mechanism undertaken by all music platforms so that only legitimate music is available. This is to clear legal rights in a similar way that collecting agencies collect royalties on behalf of artists. One way this can be solved is through compulsory licensing as this can stop the incentive to misuse an artist’s work as more people will be faced with harsher consequences.

A copyright enforcement system known as digital right’s management (DRM) [15] was introduced partly to restrict the consumers control over copying, converting, or accessing artists’ work. For example, the original iTunes fair play system stopped consumers from installing artists’ music on more than five authorized computers and WindowsPlayForSure only plays songs downloaded from Walmart Music. These practices are there to stop unauthorised distribution, reducing the amount of online piracy and potentially increase profits for the copyright holders. So, using this technological advancement is one way of blocking the potential infringement activity.

However, DRM is problematic [15] because it increases the amount legal users must pay for an artist’s work. This means legal consumers suffer because they are the ones paying the price, whereas illegal consumers remain unaffected as the pirated product does not have DRM restrictions. Hence, those who are against DRM believe legal users are more willing to pay for artists’ work if DRM was abolished because the value of buying artists’ work is higher, increasing profits for the music platform. Also, DRM can be harmful to legal users because it can limit usage of music to specific devices and if the user’s computer crashes, then they could lose all their other legal music purchases. These music platforms will have to accept the loss of profit to make sure they protect artists’ rights and stop infringement activity, even at the expense of legal users who are forced to take the burden of higher costs.

Therefore, if the online music industry could stop the leaking of music, then it would be a safer space for artists to express their musical creativity without the worries someone would steal their work, and moreover, make more profit from it. Also, new music delivery systems adopted by every music platform could be explored further as a workable solution to combat consumer habits of illegal downloading.

INCREASING VALUE FOR RIGHTS HOLDERS FOR AI GENERATED MUSIC

Stability AI and its launch of Stable Audio, known for AI text-to-image generator, is a good example of where the algorithm has been trained on licensed content [23]. It is argued that AI increases value for rights holders because their music may be used in many AI generated music because it can be modified or adapted for new use cases in countless different ways.

Meanwhile, when Beethoven died in March 1827 a part of his legacy were 40 sketches for a 10th unfinished symphony [16]. A team of experts in machine learning and musicology used those sketches to create an AI to finish what the master never could. If Beethoven were alive today, what would he, as the music rights holder, say to the exploitation of his creative works by AI to generate these finished works. In this context where his sketches were input into AI algorithm to train it to generate an output (the 10th symphony), would this be a breach of copyright laws, especially if commercially exploited.

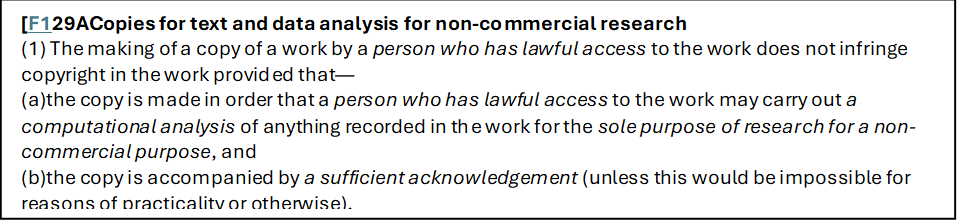

The existing copyright framework, see section 29A, Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988 [17], as copied below, is relevant here and is the TDM exception which is very narrow in scope.

In this case, it seems Beethoven arguably could assert his rights especially if his intent was always to create the finished works. The research here would be commercially driven but what about the outputs of the research (here the finished symphony) that would not be covered under the TDM exception unless inputs and outputs considered “research” under the TDM.

There are no restrictions on how or where outputs of TDM can be published, including journals published for profit by academic publishers and under licences that permit commercial research, such as Creative Commons or CC licenses [29]. This seems to be a gap area. Other commercialisation of the research outputs is not restricted either. But it is important to be scrupulous in assessing whether the original purpose of carrying out TDM analysis is solely non-commercial; if it is not, then researchers are very likely to be infringing copyright [18].

The Government stated [19] its intention to introduce a new general very broad copyright and database exception which would allow TDM “for any purpose”, whether commercial or non-commercial purposes, although rights holders would “still have safeguards to protect their content, including a requirement for lawful access “. This would have favoured the AI developers but meant rights holders would no longer be able to charge for UK licences for TDM of material that was already available legally. This outraged the right holders and so the government subsequently, in February 2023, retuned to the original wording [20].

However, whilst no formal draft of the exception was published, the requirement for lawful access would have meant that rights holders would be able to choose the platform on which they make their works available, and the basis upon which they charge for access.

On July 2023, the government said [21] it would work with users and rights holders to produce a “code of practice by the summer [2023]” on TDM by AI. The committee also warned against the use of AI to generate, reproduce, and distribute creative works and image likenesses which went against the rights of performers and the original creators of the work. Meanwhile, we await a resolution from the government and/or industry.

There are several court challenges underway on the use of existing written content and images to train generative AI. We can gain some insights into alternative approaches to practical steps for safeguarding, such as ones cited by the Society of Authors [22]. Also, there is the provisional EU Data Act reached on 27th June 2023 for non-personal industrial data to address any (IoT /cloud services) data sharing by granting rights to access, and balancing data access and trade secret protection. Data can be withheld to protect a trade secret on a case-by-case basis for serious and irreparable economic losses which is a high threshold. However, the EU Data Act excludes data processed through complex proprietary algorithms. We can await the territorial scope to the UK albeit UK Data Protection and Info Bill (Part 3).

CONCLUSION

Streaming companies, as the tech disruptors, have irreversibly changed the music industry and the sale of vinyl records and CD’s will never return to the sales of the former days with direct-to-artist payments. Record labels have lost their big revenues here and especially when record labels are no longer needed by the artists going independent.

Artists have been given an opportunity to express their creativity more than ever before and using more social media platforms, heightening artists’ influence more than before, and especially with Gen2/GenAlpha leading the music industry and the generation of AI music. More problems will inevitably result from a larger music artist population asserting more rights and compensation.

Many ways have been explored to uplift compensation due to artists whilst retaining control of their creative work.

Transparency, clarity, and balance is required amongst the actors for the largest percentage of compensation

A balanced approach is needed to reconsider the requirements of all actors for fair compensation based on their respective contribution.

Transparency is required from record labels and streaming companies about how they do their calculations for artists’ royalties over the chain of copyright title of music works. Artists receiving only about 13% of total revenue derived from their works is not fair compensation when tech platforms take 30% and record labels keep 55% of artists revenue.

Broad Industry Alignment to the User-Centric model and new Artist-Centric business model

There is an uneven power between artists, streaming platforms, and record labels, and the preferred business model needs to tip the dominance to favour the artist.

The Pro-Rata model, the one big pot royalty model where majority of money is paid by subscribers pooled favouring most listened tracks, should move to the User-Centric model based on individual consumer choices.

Broad industry alignment required to the User-Centric model as a step forward for the music industry. Universal Music’s deal recently struck with the tech disruptor streaming companies is a good start with a 10% uplift or two thirds of every dollar they collect from Deezer, based on users listening times/number of streams, providing only for professional human artists (not AI generated) and no payments for “noise”.

Profitability of all genres should be ensured and here the User-Centric model benefits the whole music field. The next generation of music makers or new talent must not be left behind if they do not fall into a class of professional artists and may be considered as “noise”. Arguably, before streaming the greater number of actors in multiple party contribution resulted in better music selection and less desirable music or noise.

Spotify could also improve their ad paid compensation to uplift their compensation to artists akin to Facebook or You Tube who generate significantly more revenue here.

Tackling online piracy

Tackling illegal downloading and streaming will have a significant uplift upon artist receiving fair compensation. Artists must work with the online music platforms to find a workable delivery mechanism to stop leaking.

Intervention by courts, government, or ISPs

The law courts, the government, collecting societies, or ISPs could also help uplift the compensation due to artists. There should be more obligations for collecting societies to collect royalties on behalf of the artist, for example, BPI, IFPI, RIAA need to do more to help.

Becoming independent and new business models required

Spotify’s tip jar proposal redirected attention to direct-to-artist payments. Further, becoming independent could uplift artists compensation to maximise their own revenue and benefit from online streaming. But it is questionable whether they stand any chance of beneficial compensation against the big tech disruptors and record labels when they must take on all the tasks themselves.

Alternatively, artists could only need to pay a small access fee to use the platforms, so to maximise their potential, removing the record label middlemen could be a sensible choice in certain circumstances.

AI Generated Music licensing

Artists can uplift their compensation by asserting their rights in music generated by AI using their music by licensing their content/data. For Beethoven and protecting music created by AI where AI algorithms trained on human created data, the current IP laws have gap areas and/or are fragmented or inconsistent across different jurisdictions and struggling to keep pace with technological developments. We await industry and government to set clear guidelines and legislation.

REFERENCES

- https://musically.com/2022/06/13/153bn-2030-goldman-sachs-music-industry-revenue/

- https://www.ft.com/content/b28b97ca-a6aa-4e90-8b89-d48ccc940756

- Napster Shut Down – ABC News (go.com)

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/newsbeat-43240886

- Spotify MAUs worldwide 2019 | Statista

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/jan/02/streaming-music-industry-apple-google

- MPs to examine impact of streaming on future of music industry | Music streaming | The GuardianMagic

- Even famous musicians struggle to make a living from streaming – here’s how to change that (theconversation.com)

- https://www.fim-musicians.org/streaming-pro-rata-vs-user-centric-distribution-models/.

- https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/apr/23/spotify-tip-jar-musicians-pay-fans-donate-artists

- Is Spotify really listening to artists “Loud & Clear?” | The FADER

- https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/the-streaming-music-industry-must-switch-to-a-fair-and-logical-payout-model-there-is-no-time-to-lose

- The Rolling Stones and Tom Jones call for streaming reforms – BBC News

- https://iconcollective.edu/independent-artist-vs-signed-artist/

- Music Downloads and the Flip Side of Digital Rights Management on JSTOR

- https://www.beethovenx-ai.com/

- https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/48/section/29A

- https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/artificial-intelligence-and-ip-copyright-and-patents/artificial-intelligence-and-intellectual-property-copyright-and-patents#text-and-data-mining-tdm

- https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/artificial-intelligence-and-ip-copyright-and-patents/outcome/artificial-intelligence-and-intellectual-property-copyright-and-patents-government-response-to-consultation#conclusion-1

- https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/our-creative-future-communications-and-digital-committee-report/

- https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/artificial-intelligence-development-risks-and-regulation/

- https://www2.societyofauthors.org/2023/06/07/artificial-intelligence-practical-steps-for-members/

- https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/stability-ai-launches-text-to-music-generator-trained-on-licensed-content-via-a-partnership-with-music-library-audiosparx/

- https://www.hipgnosissongs.com

- https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/katy-perry-sells-music-rights-to-litmus-music-in-220m-deal1

- https://stability.ai/stable-diffusion

- https://ai.meta.com/llama/

- https://www.universalmusic.com/universal-music-group-and-deezer-to-launch-the-first-comprehensive-artist-centric-music-streaming-model/

- https://creativecommons.org/about/cclicenses/

- Spotify Users Statistics 2025: Subscribers & Demographics Data.

About the authors

Jansher Verscht was a student at Latymer Upper School where he conducted a yearlong extended research project as part of his dissertation on the Economics of streaming and he extensively reviewed over 100 reliable sources. He obtained excellent recognition for his work, for highlighting the review of streaming models, and creating a voice for the artists for fair compensation, especially for those genres taking a lead in driving the music trends such as Gen2 and GenAlpha. He is now studying Economics at Loughborough university.

Jansher Verscht was a student at Latymer Upper School where he conducted a yearlong extended research project as part of his dissertation on the Economics of streaming and he extensively reviewed over 100 reliable sources. He obtained excellent recognition for his work, for highlighting the review of streaming models, and creating a voice for the artists for fair compensation, especially for those genres taking a lead in driving the music trends such as Gen2 and GenAlpha. He is now studying Economics at Loughborough university.

Dr. Afzana Anwer is an experienced IP lawyer, leading on the IP front to capture, protect, defend, enforce, and exploit IP, in a broad range of multiple industry sectors for different sized companies, from the entrepreneurial start-ups, SMEs, to the multinationals and universities. She has advanced science degrees (University of Cambridge/Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and legal qualifications in the U.S/Massachusetts and in the U.K (Roll of Solicitors).

Dr. Afzana Anwer is an experienced IP lawyer, leading on the IP front to capture, protect, defend, enforce, and exploit IP, in a broad range of multiple industry sectors for different sized companies, from the entrepreneurial start-ups, SMEs, to the multinationals and universities. She has advanced science degrees (University of Cambridge/Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and legal qualifications in the U.S/Massachusetts and in the U.K (Roll of Solicitors).