Mastering the Machinery of IP in Module 4 CEIPI MIPLM: Organizational Theory Meets IP Management

In a world where intangible assets determine market leadership, the effective management and strategic deployment of Intellectual Property (IP) are no longer niche concerns—they’re central to business success. This blog post dives into the fourth module of the CEIPI MIPLM program, which explores how the principles of New Institutional Economics (NIE) underpin the structure and organization of IP management in modern enterprises. We’ll unravel the theory and zoom in on its practical relevance—from the mechanics of an IP license agreement to agile models of innovation and IP governance.

New Institutional Economics (NIE): The Theoretical Backbone of Modern IP Organization

At the heart of this module is the New Institutional Economics, a powerful framework that explains why companies exist, how they are structured, and how they function in relation to IP. NIE is especially relevant in environments where the stakes involve high-value intangible assets and strategic uncertainty—classic traits of the IP domain.

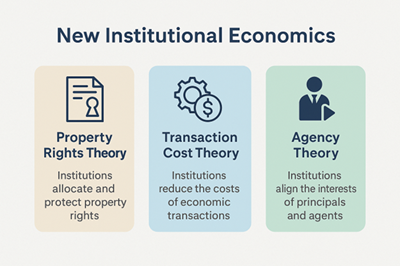

Three core theories form the pillars of NIE:

Property Rights Theory

This theory posits that institutions—laws, contracts, norms—exist to define and allocate property rights. These include the rights to use (usus), to change (abusus), to benefit (usus fructus), and to transfer (alienation) a resource. When these rights are concentrated in a single party, it maximizes the incentive to manage the resource efficiently, as they also internalize external effects (like pollution or misuse).

In IP, these rights determine who can exploit a patent, trademark, or copyright—and how. For example, patents incentivize R&D by granting inventors exclusionary rights. This forms the basis for licensing, litigation, or commercialization strategies.

Transaction Cost Theory

Ronald Coase and Oliver Williamson argued that markets aren’t frictionless. Every transaction comes with costs—finding information, negotiating contracts, ensuring compliance, and so on. Firms arise when internal organization offers a more cost-effective alternative than using markets.

In IP, this theory is vital when deciding whether to license a technology (market transaction) or develop it in-house (internal transaction). Transaction costs are influenced by asset specificity, uncertainty, and frequency. High IP litigation costs and secrecy concerns often push firms toward internal R&D or controlled licensing environments.

Agency Theory

This theory addresses the problems that arise when one party (the principal) delegates work to another (the agent) who may not have aligned interests. Think of shareholders (principals) relying on managers (agents) or, in IP terms, companies relying on external law firms or inventors.

This theory addresses the problems that arise when one party (the principal) delegates work to another (the agent) who may not have aligned interests. Think of shareholders (principals) relying on managers (agents) or, in IP terms, companies relying on external law firms or inventors.

Agency problems in IP show up in “hidden actions” (moral hazard) or “hidden intentions” (hold-up problems in licensing). Contracts and organizational structures must be designed to align incentives—e.g., performance-based royalties or milestone payments in license agreements.

Here You find Institutional Economics in the 🔎𝗜𝗣 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗚𝗹𝗼𝘀𝘀𝗮𝗿𝘆

Why Understanding NIE Is Crucial for IP Management – The Case of Licensing

Let’s bring theory to life.

Consider an IP license agreement for a branded technology product. Here’s how the three NIE theories apply:

- Property Rights Theory ensures that both licensor and licensee understand the scope of rights being transferred—use, modify, sublicense, enforce, etc. Clearly assigning these rights is critical to avoid disputes and misaligned incentives.

- Transaction Cost Theory helps in designing the contract to minimize enforcement and coordination costs. If a license requires extensive cooperation (e.g., technical support), costs can escalate unless proper governance mechanisms—like regular reviews or IP audits—are built in.

Agency Theory is used to align incentives between the licensor and licensee. For instance, royalty structures tied to sales ensure the licensee promotes the product. Quality assurance clauses ensure the licensee doesn’t tarnish the brand or IP.

Agency Theory is used to align incentives between the licensor and licensee. For instance, royalty structures tied to sales ensure the licensee promotes the product. Quality assurance clauses ensure the licensee doesn’t tarnish the brand or IP.

In sum, a well-structured license agreement is a textbook case of institutional economic theory in action.

Here you find an NIE analysis of Licensing Contracts in the 📑𝗜𝗣 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗟𝗲𝘁𝘁𝗲𝗿𝘀

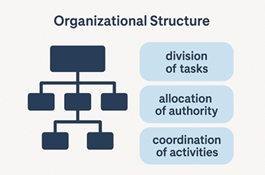

Organizational Structures: From Hierarchies to Networks

How a company organizes its resources and responsibilities profoundly affects its IP capabilities. Module 4 of the MIPLM program examines classical and modern organizational structures and their impact on IP work.

Traditional Organizational Structures

- Functional Structure: Departments are organized by expertise (e.g., R&D, marketing, legal, IP). Efficient for specialization but can create silos that hinder innovation or cross-functional collaboration.

- Divisional Structure: Organized around products, geographies, or customer segments. Better for accountability and responsiveness but may duplicate IP efforts.

- Matrix Structure: Combines functional and divisional advantages, enabling better collaboration at the cost of complexity and possible role conflict.

- Team-Based Structure: Dynamic teams form around projects. Useful in IP-heavy environments where innovation is fluid.

- Network Structure: Firms outsource many functions but remain the hub for coordination. Particularly relevant in IP ecosystems involving open innovation, joint ventures, or patent pools.

Each structure has implications for how IP is identified, protected, and commercialized. For instance, in a functional setup, the IP team may be deeply integrated with R&D, while in a divisional model, IP tasks may be decentralized and more market-focused.

Delegation and Hierarchy

Authority in traditional organizations flows top-down. Decisions around IP—e.g., filing patents or enforcing rights—may be centralized (e.g., in corporate IP departments) or decentralized (e.g., left to business units).

Authority in traditional organizations flows top-down. Decisions around IP—e.g., filing patents or enforcing rights—may be centralized (e.g., in corporate IP departments) or decentralized (e.g., left to business units).

A key insight from NIE is the principle of subsidiarity: decisions should be made at the lowest possible level without sacrificing quality. This reduces coordination costs and improves agility.

Agile IP Management: Navigating Complexity with Ambidexterity

Today’s innovation environments demand agility. Traditional hierarchies often fail in fast-moving markets where innovation cycles are short and IP risks are high. That’s where agile and ambidextrous organizations come in.

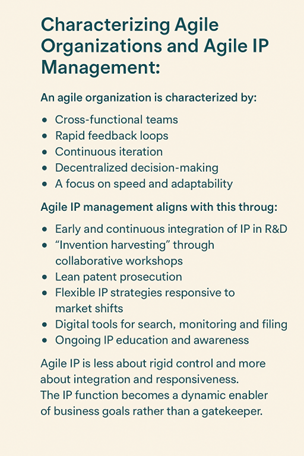

The Agile Organization

An agile organization is characterized by:

- Cross-functional teams

These teams combine diverse skill sets from different departments to tackle challenges collaboratively. This approach breaks down silos and encourages innovation through shared ownership and communication. - Rapid feedback loops

Fast feedback cycles allow teams to test, learn, and adjust quickly. This accelerates improvement and helps avoid costly mistakes early in the process. - Continuous iteration

Projects evolve through regular refinements rather than large, infrequent changes. This makes the process more flexible and aligned with real-world development - Decentralized decision-making

Decision-making power is distributed across the organization, enabling faster responses and higher employee engagement. It reduces delays caused by hierarchical approval processes. - A focus on speed and adaptability

Agile organizations prioritize quick reactions to change and the ability to shift direction as needed. This ensures they stay competitive in rapidly evolving markets.

Here you find the entry for agile organization in the 🔎𝗜𝗣 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗚𝗹𝗼𝘀𝘀𝗮𝗿𝘆

Agile IP management aligns with this through:

- Early and continuous integration of IP in R&D

IP considerations are included from the beginning of the innovation process. This ensures valuable inventions are identified and protected in time. - “Invention harvesting” through collaborative workshops

Workshops bring together inventors, legal experts, and business teams to identify and define IP opportunities. This improves both the quality and relevance of IP filings. - Lean patent prosecution

Only strategically important patents are pursued, reducing cost and administrative burden. This streamlines the patenting process and avoids portfolio clutter. - Flexible IP strategies responsive to market shift

IP portfolios are adjusted as business needs evolve. This maintains alignment between IP assets and commercial goals. - Digital tools for search, monitoring, and filing

Automation and analytics tools improve efficiency and accuracy in IP processes. They also support better decision-making through real-time data. - Ongoing IP education and awareness

Employees receive training to understand IP’s strategic importance. This creates a culture of innovation and IP responsibility throughout the organization.

Agile IP is less about rigid control and more about integration and responsiveness. The IP function becomes a dynamic enabler of business goals rather than a gatekeeper.

Ambidextrous Organizations: Innovating Today and Tomorrow

Ambidexterity means balancing two contradictory goals:

- Exploitation: Maximizing current business through incremental innovations and efficient IP protection.

- Exploration: Creating radical innovations, often requiring novel IP strategies and risk tolerance.

To do this, companies set up structurally independent units—each with its own culture and processes—but link them through shared leadership, vision, and values.

Here you find the entry for ambidextrous organization in the 🔎𝗜𝗣 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗚𝗹𝗼𝘀𝘀𝗮𝗿𝘆

An ambidextrous IP function supports both sides:

- It rigorously manages the existing portfolio (e.g., cost control, enforcement).

- It supports radical innovation via synthetic inventing, strategic patenting, and scenario planning.

For example, the IP team might work closely with R&D on future tech roadmaps while also negotiating licenses or enforcing patents on legacy products.

IP Subject Matter Experts were discussed as best practice in the 4th module of the CEIPI IP Law and Management Master-Class:

Ilanit Appelfeld: Speaking the Language of Business

Ilanit Appelfeld: Speaking the Language of Business

IP discussions need to be framed in business terms that resonated with C-suite executives and board members. Instead of focusing solely on technical or legal aspects, the IP manager needs to learn to articulate the value of IP in terms of costs, profits, margins, value creation, growth, and competitiveness.

Here the blog post by Ilanit Appelfeld

Bas Albers: Identification and Documentation

Bas Albers: Identification and Documentation

The foundation of any IP strategy begins with identifying and cataloguing all IP assets within an organization. This includes patents for inventions, trademarks for brand identity, copyrights for creative works, and trade secrets for confidential business information.

Documentation involves recording ownership details, registration statuses, and associated legal rights. Early identification ensures no valuable IP is overlooked and provides clarity on which assets require protection or commercialization.

Here the digital IP lexicon 🔗𝗱𝗜𝗣𝗹𝗲𝘅 page by Bas Albers

Adam Novak: Digitalization and the Transformation of Organizations

Adam Novak: Digitalization and the Transformation of Organizations

Digitalization is driving innovation and causing significant changes in organizations, institutions, and society. Digital technologies are also changing client behaviour and expectations. Therefore, law firms are employing more and more digital tools to fulfil the expectations of younger clients and to streamline interactions with clients.

Here the blog post by Adam Novak

Final Thoughts: A Strategic Asset Needs a Strategic Organization

The key takeaway from Module 4 of the MIPLM program is clear: the management of IP is not just a legal or technical function. It’s an organizational challenge deeply tied to how institutions, incentives, and structures interact. Whether negotiating a license, designing an IP department, or building agile innovation systems, professionals must understand and apply the principles of New Institutional Economics.

Effective IP management requires:

Effective IP management requires:

- Clarity in property rights

- Minimization of transaction and agency costs

- Structures that support both control and flexibility

- Integration of IP strategy into broader business goals

As businesses evolve to compete in global, innovation-driven markets, mastering these principles isn’t just useful—it’s essential.

Picture by Jason Goodman on Unsplash