Decision making and valuation: CEIPI MIPLM 2022-23

Decision making is a big part of management. But are managers good in making decisions? Rational or sound decision making is taken as primary function of management. Every manager takes hundreds of decisions subconsciously or consciously making it the key component in the role of a manager. Evidence- and fact-based decision making seems both desirable and rational. Concurrently, technological advances for improving decision making reopen issues related to facts, biases, and beliefs. For many years, decision support systems and technologies have had the goal of enhancing the effectiveness of human decision-making processes, fostering rational thinking, and avoiding biases and errors.

In the second module of the master class in IP management we discussed the relationship between effective and rational decision making and valuation, especially intangible asset, patent and trademark/brand valuation.

We started with decision making in a VUCA world. Across many industries, a rising tide of VUCA-characteristic, like volatility, uncertainty and business complexity is shaking markets and changing the nature and rules of competition. VUCA is an acronym which made its way into the business lexicon. The different components have been variously used to describe an environment which defies confident diagnosis and befuddles executives. But is it true, that VUCA conditions render useless any effort to understand the future and to plan responses, in short to implement strategies and to value assets? From an economist standpoint this means managing uncertainty. This leads to strategic anticipation (e.g. flexible planning), navigational leadership, agility, resilience, collaboration, and learning. And, to focus on the implications of uncertainty relative to strategy, the need to consider increasing speed, interconnectivity, cyber-attacks as just a few considerations defining a wide-ranging view of the future. During the lecture four levels of uncertainty where discussed: clear single view of the future, alternative-limited set of outcomes, range and ambiguity. And tools which can be applied like decision theory and game theory.

On November 1989, the Berlin Wall began coming down. It had symbolized the Cold war and the birth of game theory. Though conventional wars between “client states” killed thousands worldwide, guided by the game theory-based concept of mutually assured destruction, the two alliances, North Atlantic Treaty Organization and Warsaw Pact, avoided global annihilation. After 1989 the world became multipolar and much more VUCA. A stream of individually small but collectively difficult problems began fomenting at least as much fear as had the prior well understood existential cold war crisis. These problems range from climate change, increased waste production, a rising demand on resources, like rare earths for digital devices, and terrorism afflicting countries globally and triggering never-ending wars. In 1978, the US Army War College, anticipating these geo-socio-political changes, coined an acronym, VUCA, to capture their essence. Businesses co-opted the acronym around 2003 as the economic implications became obvious. Today, VUCA has become just another buzzword like “disruption”, it gets tossed around so much that it has lost its meaning, nearly. It gets added to strategy presentations but demands no change in mindset, behaviors, or action. But obviously, today we live in a digitally driven VUCA world.

The theory of social situations or from a more economic standpoint coming game theory is an accurate description of strategic interactions. Decision theory is the theory of one person games, of a game of a single player against environment. The focus is on preferences and the formation of beliefs. The most widely used form of decision theory argues that preferences among risky alternatives can be described by the maximization of the expected value of a numerical utility function, where utility may depend on a number of things, but in situations of interest to economists often depends on financial income.

Decision theory is a framework of logical and mathematical concepts, helping managers to formulate rules that lead to a most advantageous course of action, based on a strategy under given circumstances. This theoretical and interdisciplinary approach helps to determine how decisions are made given unknown variables and an uncertain environment. This is, what IP managers need to know for a “VUCA world” where we have to face various dimensions of “uncontrollable” environment. VUCA is an acronym and stands for Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous. This environmental conditions in many businesses have concrete consequences for management, especially for decision making in IP management. Decision theory brings together psychology, statistics, philosophy and mathematics to analyze the decision-making process. Also discussed in this module is game theory, which explains social situations for example between competitors. Game theory is a framework for social situations among competing players. It is the science of strategy and optimal decision making of independent and competing actors in a strategic setting.

The second part of the module was dedicated to understanding decision making and valuation. Companies create value through their operations. Managers consider operational excellence as a key ability to maximize firm value. But within the digital transformation, globalization, innovation and the ongoing war for talents the firm performance depends critically on a company’s ability to accurately determine its value and to assess the market impact of its IP. IP managers need valuation expertise to understand structured and systematic value creation with IP.

In our complex world, companies need to develop an increasing understanding on how they create value for stakeholders and society at large, to be able to develop a long-term, viable strategy and to keep their license to operate. Value creation, however, is only partially captured by a company’s financial statements, since the latter mainly reflect its financial and manufactured capital. Other forms of capital, such as social, human, intellectual and natural capital, are only partially or not visible at all in a company’s financial accounts. Since these forms of capital often remain invisible, the question arises whether companies, and their stakeholders, have the right information base to make decisions and mitigate risks that could affect their overall value creation. Three quarters of the purchase price in M&A deals is represented by goodwill and intangible assets according to the 2017 Purchase Price Allocation Study from PPAnalyser. The report highlights the importance of identifying and measuring the value of intangible assets to support the rationale of an acquisition.

Intangibles – e.g. trading names, trademarks, brand names, patents, licenses, know-how, the author’s intellectual rights – can appear in all dimensions of business activity: distribution, financial services, sales and management. Usually, intangibles generate added value that exceeds the costs attributed to them and they cannot be replaced in a short time. Generally, the intangibles contribute to the growth of sales or the reduction of costs, and consequently they raise and enhance the value of the business.

Intangibles – e.g. trading names, trademarks, brand names, patents, licenses, know-how, the author’s intellectual rights – can appear in all dimensions of business activity: distribution, financial services, sales and management. Usually, intangibles generate added value that exceeds the costs attributed to them and they cannot be replaced in a short time. Generally, the intangibles contribute to the growth of sales or the reduction of costs, and consequently they raise and enhance the value of the business.

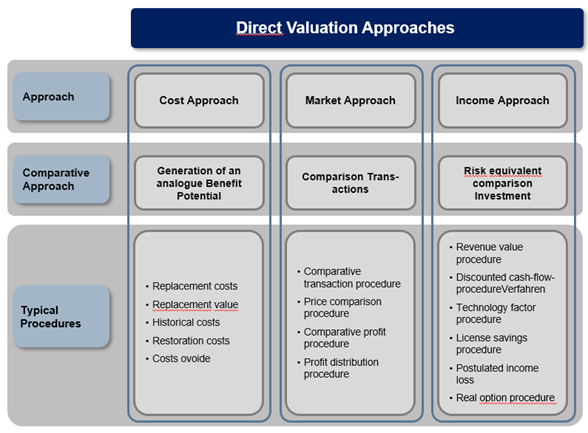

The valuation of intangibles exhibits many similarities to business appraisal. Three traditional approaches are used in the valuation of intangibles: income, cost and market. Taking into account the frequent lack of market data, the valuation of intangibles is usually limited to two approaches: cost (sometimes limited by access to historical data) and income.

A general profile of the three universally accepted approaches to the appraisal of intangibles:

The market approach (comparative) – the value of intangibles is estimated on the basis of comparable market transactions. As the intangibles are rather seldom sold separately from the enterprise itself and it is hard to find comparable assets being traded on an active market, use of this method is possible in practice only in limited cases.

The cost approach – the value of intangibles is estimated as the cost necessary to produce the asset or to replace it.

The income approach – the income approach takes into consideration potential revenues, expenses, profitability and investment expenditures related to the appraised intangible asset. This approach estimates the value of an intangible asset as the present value or capitalization of future cash flows, sales or saved costs over the period of the economic life of the intangible asset.

The income approach is perceived as the basic approach in the valuation of intangibles in the majority of cases. The income approach can take various methods depending on the unique character of the appraisal process of the intangible. The main income methods are as follows:

- Relief from royalties method

- Excess rate of return method

- Postulated loss of income method

- Discounted cash flow approach