Domain Wars: EUIPO Discussion Paper

With the ever-growing internet and more and more companies starting their online business, the availability for premium domains becomes smaller and the battles become fiercer. There are millions of websites, all with unique domain names. In such a crowded market, you may find that somebody else already owns and is using a domain for which you have the trademark. Companies who have registered a domain name that is perfect for their business sometimes receive a letter from a law firm alleging that their domain name infringes someone else’s trademark, or even worse, receive a complaint made against them under the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP), which if the trademark holder (Complainant) is successful, allows the Complainant to take possession of your domain name.

Domain name disputes seem to be all the rage these days. With some domain names selling for millions of dollars, it is no wonder that there are several very famous domain name disputes. From entertainment to politics to the unfortunate high school teenager, domain name disputes do not fail to entertain. For example:

- Bruce Springsteen vs. BruceSpringsteen.com

- City of Quebec vs. Quebec.com

- Microsoft vs. MikeRoweSoft

Domain names can be registered through many different companies – known as “registrars” that compete with one another. All ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) accredited registrars follow a UDRP (Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy). Under that policy, disputes over entitlement to a domain-name registration are ordinarily resolved by court litigation between the parties claiming rights to the registration. Once the courts rule who is entitled to the registration, the registrar will implement that ruling. In disputes arising from registrations allegedly made abusively (such as “cybersquatting” and “cyberpiracy”), the uniform policy provides an expedited administrative procedure to allow the dispute to be resolved without the cost and delays often encountered in court litigation. In these cases, you can invoke the administrative procedure by filing a complaint with one of the dispute-resolution service providers.

The UDRP Policy applies to .com, .net and .org, extensions as well as to a number of more recently introduced gTLDs (generic Top Level Domains), such as .aero, .asia, .biz, .cat, .coop, .info, .jobs, .mobi, .museum, .name, .pro, .travel and .tel. Since commencing its UDRP service, WIPO has processed some 27,000 UDRP and UDRP-related cases. In several cases decided under the UDRP Policy, panels from the WIPO ordered the transfer or cancellation of the infringing domain name.

Tackling bad faith registration of domain names in a fast-changing landscape

The “Dot Com” boom of the late 1990s ushered in the commercialization of the Internet and spawned the expansion of the domain name system. These positive developments, however, also gave rise to the problem of cybersquatting – the bad faith registration of domain names, especially well-known trademarks, in the hope of reselling them at a profit.

Acknowledging the threat that cybersquatting represented to consumer trust and to the safety, security, and stability of the Internet, in the late 1990s the United States Government asked the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) to conduct a consultative study on domain name and trademark issues and to develop recommendations to combat related online abuses. WIPO’s recommendations culminated in the UDRP, which has proven to be a highly successful and effective online tool for protecting brand owners’ rights and for building consumer confidence in global e-commerce.

In April 1999, WIPO presented its report to the then-newly-formed Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) recommending a quick, efficient, cost-effective and uniform procedure to address cybersquatting. The WIPO Report also provided forward-looking recommendations on registrant contact information, a topic that ICANN is only now addressing following the implementation of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). In the six months following the launch of the WIPO report, the ICANN community, through its multi-stakeholder policy development process, made a few minor changes to WIPO’s proposed policy.

The UDRP requires a complainant to establish three elements, namely, that:

- the domain name is confusingly similar to the complainant’s trademark;

- the registrant has no rights or legitimate interests in the domain name; and that

- the domain name has been registered and is being used in “bad faith”.

A successful UDRP complainant can elect either to have the disputed domain name transferred to its control, or to have it cancelled. The UDRP was adopted as a binding “consensus policy” (meaning the UDRP was required to be implemented by registries and registrars to all ICANN-managed domains, such as “.com”) by the ICANN Board in October 1999. A month later, the WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center (“the WIPO Center”) became the first accredited UDRP dispute-resolution service provider, and in December 1999, the first domain name case was filed with the WIPO Center.

Today, brand owners and Internet users contend with issues such as the misuse of domain names to further the sale of counterfeit products, phishing schemes and fraud. In 2019, 16 percent of domain name cases filed with the WIPO Center involved instances of phishing schemes, 8 percent of cases involved an allegation of fraud and nearly 6 percent of them involved the sale of counterfeit goods or services. Two-thirds of the cases related to counterfeit products involved the fashion, retail and luxury goods industries. The banking industry was the primary target for both fraud and phishing schemes, accounting respectively for 21 percent and 34 percent of cases handled by the WIPO Center in 2019.

EUIPO Expert Group on “Cooperation with intermediaries” discussion paper

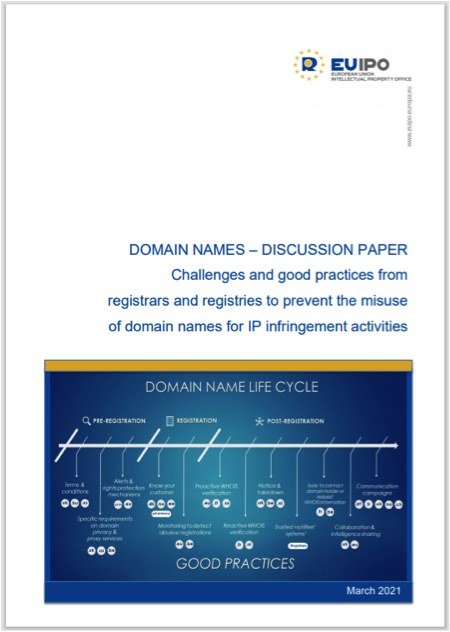

The Expert Group on “Cooperation with intermediaries” was set up to further the understanding of different intermediary services, how they can be misused for IP-infringing activities, and what the good practices are to undermine such misuses. This first discussion paper looks into Domain Names. It will hopefully contribute to a better understanding of the domain name eco-system, the good practices that are developing to prevent the misuse of domain names for IP-infringing activities, and the challenges and opportunities to extend or replicate some of these good practices.

The Expert Group on “Cooperation with intermediaries” was set up to further the understanding of different intermediary services, how they can be misused for IP-infringing activities, and what the good practices are to undermine such misuses. This first discussion paper looks into Domain Names. It will hopefully contribute to a better understanding of the domain name eco-system, the good practices that are developing to prevent the misuse of domain names for IP-infringing activities, and the challenges and opportunities to extend or replicate some of these good practices.

This discussion paper provides an overview of the good practices that can help prevent the misuse of domain names for IP-infringing activities. This is the case when IP rights are misused in the name of the domain itself (i.e. cybersquatting or typosquatting) or when the domain name leads to a website supporting IP-infringing activities.