Superfakes: The New Level of Deception

The allure of luxury goods has never been stronger. From designer handbags to high-end sneakers, the desire to own prestigious brands permeates our culture. You have heard of counterfeit products before, but the so-called “superfakes” take deception to a whole new level. But what exactly are superfakes, and why are they causing such a stir? In this article, I would like to address exactly that.

Put simple, a superfake is a fake which is so good that probably only you will know that it is not a real deal. Frequently, it will use the very same (or almost the same) materials as in the real item and have every single bit of detailing one would expect. And a logo of luxury brand, of course. These meticulously crafted replicas are so eerily similar to the real thing that even experts struggle to tell them apart. As to the pricing, one won’t be able to get a superfake for 20-30 euros, but EUR 100-300 for something usually priced at EUR 3.000 is quite possible. Everything one could wish for, right? Except that Hermes, Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Dior, Gucci or Celine had nothing to do with it.

In September last year, The Style Magazine came out with an article with a long self-explanatory title: “Inside the rise of the superfake handbag: from Gucci knock-offs and Dior dupes, to Hermès Birkins that look just like the real thing, copycat manufacturers are scarily good – and Gen Z loves it”[1]. The article claims that Chinese manufacturers are nowadays replicating designer items in such a detail “that even the most experienced authenticators can struggle to decipher a superfake”. Furthermore, as the reference goes to Gen-Z’s, this customer category according to the article, does not shy away from fakes, doesn’t consider them a taboo and even, on the contrary, wear them with pride. This is attributed to the push coming from the social media, such as e.g. TikTok where one can come across countless videos about… how to find the perfect superfake.

Several months before the mentioned article in The Style Magazine, also The New York Times Magazine came out with the article “Inside the Delirious Rise of “Superfake” Handbags”[2]. The author, Amy X. Wang, described her experience purchasing superfakes, which is also apparently done by wealthy women who could easily afford the original. She writes – and I would like to quote her literally:

“There is a smug superiority that comes with luxury bags — that’s sort of the point — but to my surprise, I found that this was even more the case with superfakes. Paradoxically, while there’s nothing more quotidian than a fake bag that comes out of a makeshift factory of nameless laborers studying how to replicate someone else’s idea, in another sense, there’s nothing more original.”

One could further unpack the above quote from many standpoints, but I will just leave it be – read it once again and make your own conclusions, while I move on.

So, superfakes are as good as real things. What’s the problem? The problem is multi-faceted. Let’s start with consumers, and here I jump directly into psychology.

Perspective of consumers

Why are consumers attracted to superfakes in the first place?

In a society where image and perception hold considerable sway, owning a luxury item – even if it’s a counterfeit – can serve as a symbol of success and social standing, a form of self-expression and identity construction. By owning counterfeit versions of coveted designer goods, individuals can craft a carefully curated image of themselves as affluent, sophisticated, and stylish – qualities that are still highly valued in our consumer-driven society. At a fraction of a cost. This quest to project a desirable image to others, coupled with the thrill of acquiring a coveted item significantly cheaper, fuels the allure of superfakes and drives consumer behavior.

With authentic luxury often out of reach due to exorbitant price tags, superfakes emerge as a tempting solution. These high-quality replicas, meticulously crafted with genuine materials, offer the allure of luxury without the crippling financial burden. In essence, it’s a way to “have your cake and eat it too.” Unlike their low-quality counterparts riddled with cheap materials and obvious flaws, superfakes make no compromises on quality. This, for many, is a key selling point.

Additionally, the psychology of scarcity plays a significant role in driving demand for superfakes. Luxury brands carefully cultivate an aura of exclusivity and rarity around their products, creating a sense of urgency and desire among consumers (for as long as it holds, given that e.g. Hermes sales tactics are currently being challenged in court)[3]. Superfakes offer a way to bypass these barriers to access imposed by luxury brands, allowing individuals to experience the same sense of exclusivity and prestige without the need to wait (or save up). One could even bring this argument further: if getting a real Birkin is made so problematic, why bother and not just settle for a superfake one?

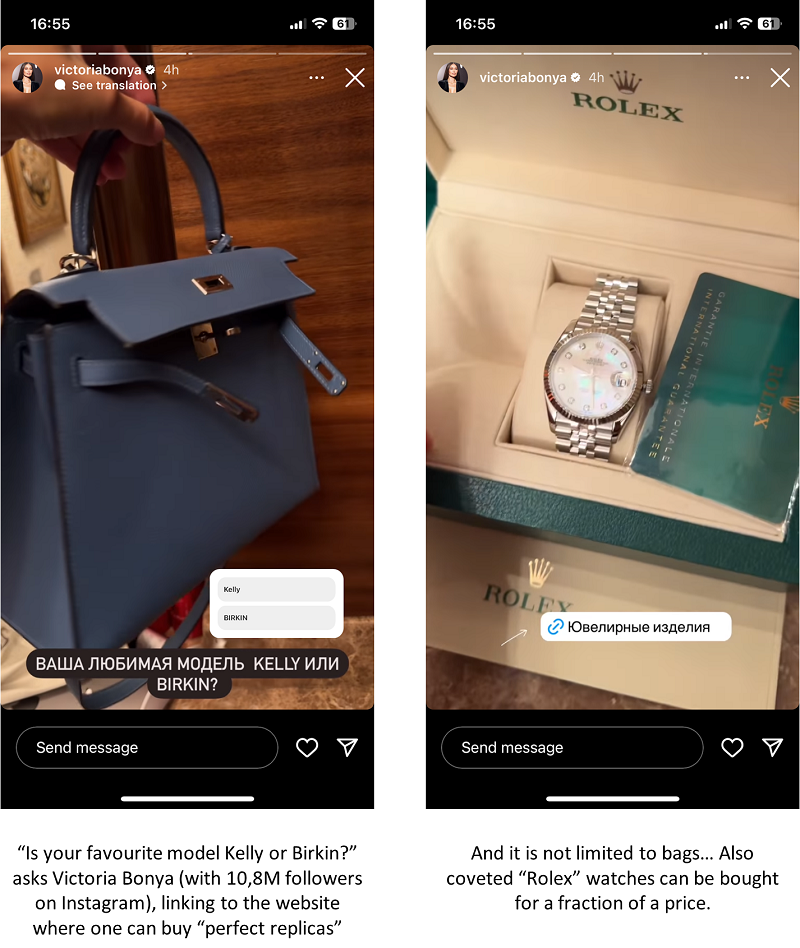

Further compounding the issue, influencers and content creators often normalize, if not glamorize, superfakes, promoting these seemingly luxurious lifestyles. This normalization of counterfeit culture fuels a dangerous cycle of counterfeit acceptance, blurring the lines between genuine and fake. Bombarded with images of peers sporting counterfeits, impressionable young consumers internalize the message that authenticity is secondary – it’s the appearance that counts.

Therefore, in essence, the allure of superfakes is rooted in the complex interplay of social, emotional, and cognitive factors that shape human behavior. And there you have it… The problem is, however, that superfakes are violating luxury brands’ Intellectual Property (IP) rights. But then again, how many consumers are actually aware of IP rights? And how many of them care?

The line between blatant fakes and superfakes can be blurry. Even the (frequently used) term “replica” feels like a euphemism for a counterfeit good. Let’s be clear: a fake is a fake, regardless of terminology.

What many consumers disregard or simply don’t know is that in many countries, it is illegal to own a fake bag. Yes, that’s right! As a consumer, one can get sued for parading around swinging a fake Chanel 2.55.

Already a while ago, there was a campaign by French customs sensibilizing consumers about the risks of fines and even imprisonment for buying and using fakes:

Same laws apply in a number of other countries in Europe and beyond. In other words, while buying superfakes can be tempting, this temptation can also backfire big time.

Perspective of makers of superfakes

Taking the Devil’s Advocate stance, can superfake creators be seen as simply fulfilling a market need? After all, they offer access to luxury for those priced out of the market. In a world where material possessions influence self-worth, superfakes appear to level the playing field, allowing some to participate in the elite’s luxury lifestyle. Perhaps, this democratization of luxury is the ultimate goal?

Well, not quite.

There’s also this argument that superfake craftsmanship is commendable. The artisans’ skill in replicating high-end designs is undeniable. But then I immediately remember Han van Meegeren, the art forger whose Vermeers were so convincing they went undetected for years. His talent was undeniable, but criminal nonetheless. Skillful imitation isn’t the same as creating something original.

Another justification offered is that superfakes allow for affordable experimentation with fashion trends. Consumers can dabble in luxury without exorbitant price tags, fostering creativity and self-expression. Modern-day Robin Hoods, some might say.

In fact, during a discussion I had about this very topic, someone raised an interesting sustainability-related point: what about luxury brands burning unsold stock to protect brand image? These brands, they argued, prioritize image over sustainability, while superfake makers offer their products at a fair price. “Who’s the real villain here?” the question popped.

But regardless of justification, the truth is clear: superfakes are a form of theft.

When buying the real thing, you pay for intellectual property – the brand and design. Luxury brands invest heavily in protecting their trademarks and designs, and they have the right to set their prices. Superfake makers blatantly exploit these efforts. Hence, at its core, the superfake industry profits from stealing someone else’s intellectual property.

The bottom line?

If you see luxury brands as villains, simply don’t buy their products. But don’t support the criminal superfake industry instead.

Perspective of luxury brands

According to the article referenced in the beginning, in 2020 alone, “luxury brands reportedly lost over US$50 billion in potential sales”[4]. This is, of course, a questionable statement. One could argue that the consumers who bought superfakes would not have otherwise bought the real thing.

At the same time, superfakes do inflict real damage on luxury brands. When consumers struggle to differentiate genuine products from near-perfect replicas, brand loyalty suffers. Fear of purchasing a superfake or being mistaken for someone carrying a counterfeit can deter consumers from buying the real thing altogether. This erodes trust, not just for individual companies, but for the entire luxury industry.

Furthermore, rampant counterfeiting undermines the very essence of luxury: exclusivity and rarity. When the market is flooded with superfakes, the perceived value of genuine items plummets. The once-unattainable allure of luxury becomes diluted, essentially turning these coveted items into commodities.

Is there anything that can be done?

Combatting superfakes requires a unique strategy. Unlike easily identifiable fakes, superfakes demand a more sophisticated approach due to their near-perfect quality.

One approach luxury brands can take is to invest in advanced authentication technologies that can differentiate between genuine products and superfakes with a high degree of accuracy. This may involve incorporating features such as RFID tags, microchips, or unique serial numbers (possibly authenticated in the Blockchain) into their products, enabling consumers, retailers, and law enforcement officials to verify authenticity quickly and easily.

Additionally, luxury brands can leverage the power of data and analytics to track and identify patterns of counterfeit activity, allowing them to anticipate and preemptively address emerging threats posed by superfakes. By analyzing sales data, online reviews, and social media activity (including the actions of certain influencers), brands can pinpoint areas vulnerable to counterfeiting and prioritize their enforcement efforts.

Furthermore, luxury brands can collaborate with law enforcement agencies, industry associations, and IP experts to develop targeted enforcement strategies aimed specifically at combating superfakes. This may involve conducting sting operations to dismantle counterfeit networks, prosecuting key players involved in the production and distribution of superfakes, and advocating for stronger legal protections against IP infringement. This combines awareness building with a strong and immediate response.

Consumer education likewise plays a crucial role. Many consumers are unaware of the legal and ethical implications of purchasing superfakes. Luxury brands can take proactive steps to educate them about the dangers of counterfeit culture, highlighting the ethical and legal implications of supporting it. But above all, this might be a good moment for the luxury industry to reinvent itself to emerge stronger.

In conclusion, the rise of superfakes lays bare the web of consumerism, ethics, and intellectual property. As discerning consumers, we have the power to influence the trajectory of the fashion industry, particularly the luxury sector. Regardless of your personal stance on luxury brands, remember that superfakes are not a victimless crime. By funding them, one contributes to criminal activity and erodes the very foundations of creativity and innovation that fuel the luxury experience. Let’s not do that.

About the blogpost author:

Maria Boicova-Wynants is a partner with Starks, an IP and International trade law firm in Ghent, Belgium, and heads her own IP strategy consulting practice. She holds LL.B. from the University of Latvia, MBA from Vlerick Business School and LL.M. (MIPLM) from CEIPI. Maria is a Latvian Patent and Trademark Attorney, European Trademark and Design Attorney, as well as European Mediator in civil and commercial cross-border disputes for almost two decades. Her main areas of expertise are IP strategy, contracts, and alternative dispute resolution. She is also a mediator and art law expert on the list of the Court of Arbitration for Art (the Hague), and the Mediator on the WIPO ADR Centre’s List of neutrals.

Maria Boicova-Wynants is a partner with Starks, an IP and International trade law firm in Ghent, Belgium, and heads her own IP strategy consulting practice. She holds LL.B. from the University of Latvia, MBA from Vlerick Business School and LL.M. (MIPLM) from CEIPI. Maria is a Latvian Patent and Trademark Attorney, European Trademark and Design Attorney, as well as European Mediator in civil and commercial cross-border disputes for almost two decades. Her main areas of expertise are IP strategy, contracts, and alternative dispute resolution. She is also a mediator and art law expert on the list of the Court of Arbitration for Art (the Hague), and the Mediator on the WIPO ADR Centre’s List of neutrals.

_______________________________________

[1] https://www.scmp.com/magazines/style/fashion/trends/article/3233114/inside-rise-superfake-handbag-gucci-knock-offs-and-dior-dupes-hermes-birkins-look-just-real-thing

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/04/magazine/celine-chanel-gucci-superfake-handbags.html

[3] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/services/retail/they-failed-to-buy-birkin-bags-so-they-sued/articleshow/108754728.cms?from=mdr

[4] https://www.scmp.com/magazines/style/fashion/trends/article/3233114/inside-rise-superfake-handbag-gucci-knock-offs-and-dior-dupes-hermes-birkins-look-just-real-thing