Managing Technological Innovation in Practice: CEIPI MIPLM 2025/26 Module 3

In Module 3 of the CEIPI Master of MIPLM, the lecture on managing technological innovation takes on a problem many organizations feel but rarely name clearly: innovation needs freedom, while management needs reliability. The course does not pretend this tension disappears. Instead, it shows how to work with it by building structures that protect creativity while still producing outcomes a business can fund, scale, and defend. This lecture is curated by Prof. Dr. Alexander J. Wurzer with IP subject matter experts at the IP Business Academy Daniel Holzner, Nicos Raftis, Sascha Kamhuber and Bernd Bösherz.

The lecture’s central promise is not that innovation becomes predictable. The promise is that organizations can become better at placing structure around uncertainty. When IP is treated as part of the innovation operating system, and when timing, development discipline, and collaboration design are managed explicitly, technological innovation becomes less of a heroic accident and more of a repeatable advantage.

📌 You find the entry on Innovation Process in the 🔎𝗜𝗣 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗚𝗹𝗼𝘀𝘀𝗮𝗿𝘆 here

The core contradiction: Why innovation resists being managed

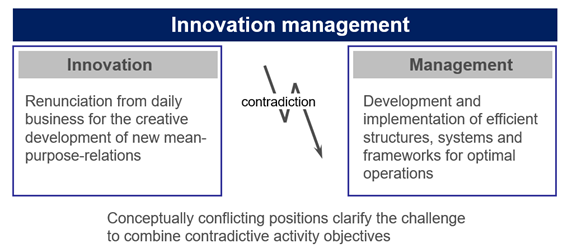

A useful starting point is the lecture’s conceptual contrast.

Innovation is framed as a temporary renunciation of daily business logic so that new means purpose relations can emerge. Management, by contrast, is about building structures, systems, and frameworks that enableefficient and repeatable operations. The contradiction is not rhetorical. It creates real friction in decision making, funding, staffing, and timing. Teams get stuck between “we need to explore” and “we need to deliver”.

What matters is the implication: if you apply only management logic, you suffocate novelty. If you apply only innovation logic, you get exciting prototypes that never become durable value. Managing technological innovation means becoming bilingual. You learn when to protect exploration from operational metrics and when to translate exploration into operational commitments.

R&D is not the whole innovation process

Another clarifying move is the differentiation between an R and D process and an innovation process.

R and D is typically systematic. It involves repeatable activities, clearer boundaries, and stronger institutionalization. That is why specialization works well there. Innovation management, however, includes many one time activities and administrative processes that do not repeat cleanly. Because innovation is not always “R and D shaped”, specialization can even become counterproductive. You need orchestration, not just optimization.

The important sentence here is simple: an R and D process is an innovation process, but an innovation process is not necessarily an R and D process. Once you accept that, you stop treating innovation as a laboratory pipeline and start treating it as a broader system that includes market sensing, complementary assets, adoption dynamics, and intellectual property decisions.

Is the management of technological innovation possible?

📌 You find the entry on IP Alignment in the 🔎𝗜𝗣 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗚𝗹𝗼𝘀𝘀𝗮𝗿𝘆 here

📌 You find the entry on IP Culture in the 🔎𝗜𝗣 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗚𝗹𝗼𝘀𝘀𝗮𝗿𝘆 here

Technology management versus innovation management: A fuzzy boundary with a sharp lesson

The lecture also addresses a classic confusion: technology management and innovation management overlap, but their priorities can conflict.

Technology management aims to preserve and develop existing technologies to ensure long term technological competitiveness. Innovation management is often forced to push next generation technologies into adoption, sometimes against the internal guardians of the current stack. The boundary is fuzzy, but the lesson is sharp: you cannot protect today’s advantage so hard that you block tomorrow’s competitiveness.

The integrated view is “strategic management of technological innovation”. Its objective is sustained securing of a technology position that optimizes company performance. The lecture emphasizes alignment with objectives, resources, and processes. That alignment is the difference between isolated invention and repeatable innovation success.

IP as a cornerstone of the innovation process

A major thread throughout the lecture is the integration of intellectual property into innovation, not as an afterthought, but as a decision making layer.

The deck highlights the familiar trio: patents, trademarks, and trade secrets, with Coca-Cola as the classic trade secret example. But the more strategic point is this: IP is a system for appropriation. It defines what you can keep exclusive, what you can safely share, and what you can monetize through licensing or partnerships.

From an innovation management perspective, IP also reduces uncertainty. It shapes investor confidence, partner negotiations, and the credibility of roadmaps. In other words, IP is not only protection. It is coordination.

Innovation Process with IP

Timing of entry: The market rarely rewards being first in the way founders imagine

The lecture’s timing of entry section is one of the most practical because it forces trade off thinking.

It defines first movers, early followers, and late entrants, then illustrates the dynamics with the personal digital assistant story, referencing Star Trek as an early conceptual origin. Early entrants including Apple, IBM, HP, GO Corporation, and EO Inc. faced immature enabling technologies such as batteries, modems, and handwriting recognition, plus unclear market definition. Later, Microsoft announced entry and stalled demand, but the delivered performance disappointed. Palm Computing then succeeded with simpler design and lower pricing, before smartphones absorbed the category.

📌 You find the 📑IP Management Letter on the rise and fall of PDAs here

The takeaway is not “first is bad” or “late is safe”. The takeaway is diagnostic thinking. The lecture provides criteria such as certainty of customer preferences, maturity of enabling technologies, availability of complementary goods, type of innovation, threat of entry, pace of adoption, and the firm’s ability to withstand early losses and accelerate market acceptance.

From an IP angle, timing is also about when to file, when to publish, when to keep secret, and when to license. A brilliant invention launched too early can still lose because the ecosystem is not ready.

A first mover analysis

Managing product development: From idea flood to disciplined selection

The lecture then moves from market timing to execution discipline. The innovation funnel is introduced with an often sobering ratio: thousands of raw ideas become a few launches and typically one successful new product. That is not pessimism. It is reality management.

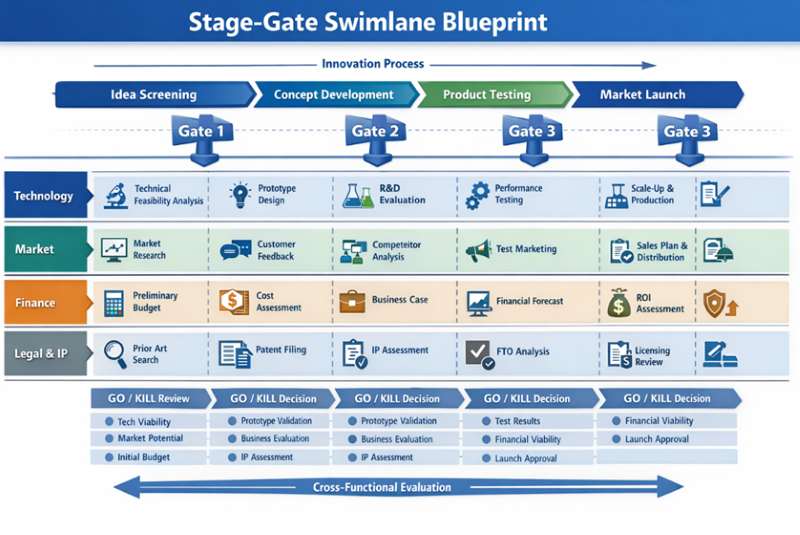

Objectives of managing product development include fit for customer requirements, early market entry when it matters, minimizing cycle time, and controlling costs so development does not exceed willingness to pay. To operationalize these objectives, the lecture highlights structured processes such as Stage Gate systems, including an example based on Exxon research and engineering. The key idea is cross functional parallel work within stages, and explicit go or kill decisions at gates based on technical, financial, and market information.

This is also where IP becomes milestone based. You do not just file at the end. You map IP decisions to the development stages, so the organization learns early whether it is building something protectable, avoidable, licensable, or strategically risky.

The stage-gate process as an instrument to manage technological innovation

📌 You find the podcast 🎧IP Management Voice episode #34 on the Power of Stage Gate Systems here

📌 You find the entry Stage-Gate Process in the 🔎𝗜𝗣 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗚𝗹𝗼𝘀𝘀𝗮𝗿𝘆 here

Two IP Subject Matter Expert contributions that make the lecture feel real

Two applied contributions stand out because they bridge lecture logic with operational methods that teams can actually use.

IP Subject Matter Expert Daniel Holzner: AI supported innovation management and AI assisted inventing

The lecture points to AI assisted invention processes such as patent landscape based white spot analysis. The value is not automation for its own sake. The value is decision support. AI can scan patent and scientific landscapes, identify underdeveloped areas with innovation potential, and reduce the risk of investing in crowded solution paths. The framework attributed to Daniel Holzner is presented as actionable methodology for navigating complex R and D landscapes. In innovation management terms, this contribution strengthens the front end of the funnel by improving the quality of exploration choices.

📌 You find the digital IP Lexicon 🧭dIPlex page by Daniel Holzner on AI-assisted invention processes here

IP Subject Matter Expert Nicos Raftis: Patent circumvention as a design capability

Competitors’ patents can constrain development choices, especially for smaller firms trying to enter markets dominated by incumbents. The lecture reframes “patent avoidance” as a strategic enabler rather than a defensive legal chore. It highlights TRIZ based approaches associated with Nicos Raftis that help teams redesign components or configurations so they bypass protected claims while still solving the underlying engineering problem. The managerial insight is powerful: constraints can become catalysts. Patent circumvention, done systematically, can reduce litigation risk and speed development by preventing late stage surprises.

📌 You find the digital IP Lexicon 🧭dIPlex page by Nicos Raftis on Inventing Around in Managed Technological Innovation here

Together, these two contributions represent a modern toolbox. One helps teams choose where to invent. The other helps teams invent around barriers when the chosen space is constrained.

Road mapping and patent information: Turning signals into strategy

The lecture also connects patent information to technology road mapping and scenario thinking. Patent analysis can identify emerging technologies and trends, which supports both emerging and product technology roadmaps. It also supports integrated roadmaps that consider technologies, applications, and market trends simultaneously.

The deck references Sascha Kamhuber as an example of using patent information to monitor global competition in the steel industry. The value here is managerial: patents become early signals of competitors’ strategic investment directions.

📌 You find the digital IP Lexicon 🧭dIPlex page by Sascha Kamhuber on Innovation in the Steel Industry here

A later case focuses on Signify and the SAILS approach for road mapping disruptive threats and opportunities, categorizing patents across standards, architectures, integration, linkages, and substitutions. This provides a structured way to interpret IP signals as strategic options.

IP Road-Mapping in managing technological innovation

Collaboration strategies: Innovation happens in networks, so IP must do the same

Finally, the lecture addresses collaboration as a core innovation lever. Collaboration offers speed, flexibility, learning, and risk and cost sharing, but it also raises IP complexity. Partners can include suppliers, competitors, complementors, universities, customers, and government organizations. The lecture outlines options such as strategic alliances, joint ventures, licensing, outsourcing, and collective research organizations, illustrating the spectrum with examples like General Electric with SNECMA, JVC with Thomson, and Nortel Networks outsourcing manufacturing.

In this lecture, the contribution of IP Subject Matter Expert Bernd Bösherz is positioned within collaborative IP management: he adds the contract architecture perspective that makes cooperation workable at scale. His point is that partnerships only remain innovation friendly when IP related roles, boundaries, and rights are defined explicitly, from early confidentiality through to commercialization. Practically, this means designing IP aware agreements, including NDAs, purchase contracts, and cooperation agreements, so that knowledge can be shared with confidence while ownership, usage rights, and exploitation paths stay clear.

📌 You find the digital IP Lexicon 🧭dIPlex page by Bernd Bösherz on Collective IP Management here

A dedicated section on collaborative IP management emphasizes that IP in collaborations is not just legal safeguarding. It is integration into business strategy so that ideas move from concept to market while value appropriation remains fair and feasible. The deck also includes a case study on IMEC, highlighting how an ecosystem orchestrator can use IP models and partner programs to stimulate cooperation while sustaining long term success.

The power of collaboration in technological innovation