Pricing the Invisible: How IP Valuation Turns Brands and Patents into Hard Numbers

Intellectual property has become one of the main engines of enterprise value. Global rankings of the “Best Global Brands” show that for companies like Apple, Microsoft or Coca-Cola, branded intangible assets account for a substantial share of market capitalization. In other industries, proprietary technology, data or algorithms play the same role. IP is no longer a side note in the balance sheet; it is often the real economic core of the business model. This post is a summary of the lecture “Brand Valuation / Value Creation by Brands” by Theo Grünewald at the CEIPI Master for IP Law and Management 2025-26.

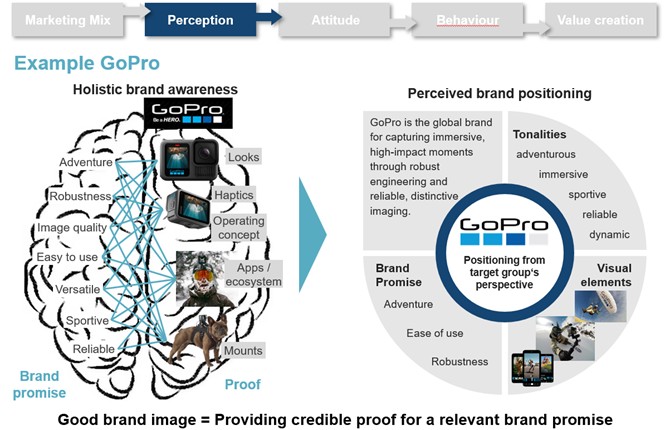

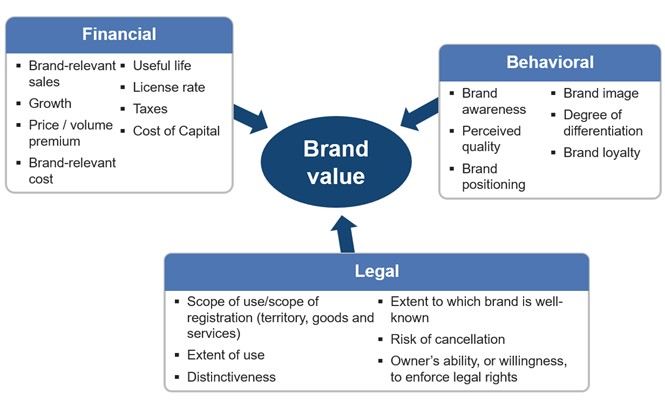

To understand why, it helps to look at the concept of a brand itself. In the IP Management Glossary entry on brand, a brand is described not just as a name or logo, but as the total bundle of associations that guide customer decisions. The related article on brand equity explains how these associations translate into preference, loyalty and ultimately superior cash flows. Valuation of IP is therefore about putting a monetary figure on these future advantages – whether they come from a brand, a patent, a design or a portfolio that combines them.

What do “value” and “valuation” mean in IP?

In IP management, value is not a static property of an asset. It is the economic benefit an owner can expect from using or licensing that asset in the future. The lecture on brand valuation emphasizes this explicitly: the private economic value of a right is determined by the future benefits the owner can extract from it, for example through price premiums, additional volumes or lower risk.

Valuation is the structured process of transforming all available information about these future benefits into a single number that is consistent, transparent and fit for a specific decision. That number is always conditional: it is valid only for a defined situation, at a certain time, under clearly stated assumptions.

This is why scenarios play such a central role. Strictly speaking, we are never valuing “the patent” or “the brand” in isolation. We are valuing a scenario in which a specific party exploits this IP right in a specific way. Change the scenario – for example from exclusive licensing to non-exclusive licensing, from a domestic launch to a global roll-out, or from a stand-alone brand to an ingredient brand – and the value can change dramatically.

Two fundamental concepts of value

From this perspective, two fundamental value concepts become important:

- Value to the owner (private economic value).

This is the present value of all future cash flows that the current owner can realise with the IP right, given the existing business model. The Dyson brand in vacuum cleaners, for example, generates higher margins than a generic competitor because customers believe the performance promise and accept a price premium. That premium, when projected and discounted, defines the value to Dyson. - Value in exchange (market or transaction value).

If the right is to be sold or licensed, the relevant question becomes: what would a hypothetical buyer pay? Here, the perspective shifts to a neutral market participant who can use the asset in the best available way. In practice, the exchange value is determined by negotiation between buyer and seller, but the bargaining range is anchored in the private economic value for both sides.

Any concrete valuation must make explicit which of these concepts it follows. Confusing them leads to unrealistic expectations – for example when a company wants a high transaction price based on its own synergy story, while potential buyers see much smaller benefits.

Approaches to patent and IP valuation

The dIPlex overview on IP valuation provides a useful map of the main approaches used in practice and in standards such as ISO 10668 or ISO 10689 for brand and patent valuation.

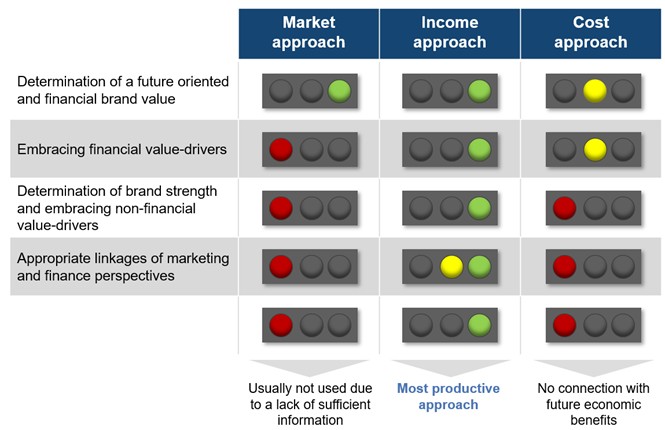

Despite different labels, three families of methods dominate:

- Cost approach

The cost approach asks what it would cost today to recreate or replace the IP right with a functionally equivalent solution. For a patent, this could be the R&D expenditure required to arrive at a similar invention and bring it to the same stage of legal protection. For a brand, it might be the historical and current marketing investments needed to build comparable awareness and loyalty.

This approach is intuitive and often used when no direct cash flows can be separated for the IP. However, the economic weakness is obvious: costs and value are not directly correlated. Many expensive R&D projects fail, while some low-cost inventions create huge value. Therefore, cost-based results are usually regarded as a floor, not as a full picture of economic value.

- Market approach

The market approach looks at observable transactions of comparable IP rights: license deals, brand sales, portfolio acquisitions. For patents, that could be deals in the same technology field with similar scope and remaining life; for brands, the lecture shows how sales multiples from real brand transactions can be applied to “branded sales” to estimate value.

The strength of this method is its anchoring in real prices. Its weakness is data quality: IP is rarely traded on transparent markets, and the details of comparable deals (scope, strength, synergies) are often confidential. Adjusting for these differences requires judgment and can erode the apparent objectivity.

- Income approach

The income approach is the workhorse of modern IP valuation. It directly models the future cash flows attributable to the IP and discounts them to present value using an appropriate risk-adjusted rate.

Three variants are widely applied:

- Incremental cash flow method: compare a business scenario with IP to a scenario without IP (for instance, a branded product versus a generic version). The difference in cash flows – price premium, volume premium, cost savings – is attributed to the IP.

- Relief-from-royalty method: assume that, if the company did not own the IP, it would licence it from a third party at a market royalty rate. The hypothetical royalty savings (after tax) become the IP cash flows.

- Multi-period excess earnings method: start from the operating income of a business and deduct “charges” for all other contributing assets (tangible assets, working capital, technology, customer relationships). The residual earnings are then attributed to the IP under analysis.

These methods connect the qualitative idea of brand equity – and, by analogy, the strategic strength of patents – with financial performance. They are also flexible enough to reflect complex scenarios, such as multi-territory licensing, staged market entry or platform technologies.

Present value, WACC and risk

All income-based valuations rely on the concept of discounted cash flow. Future cash flows must be translated into their equivalent value today. The blog post on how present value and WACC transform IP valuation gives a concise explanation of this logic and shows how discounting turns a long stream of benefits into one comparable figure.

Choosing the discount rate is crucial. The article on “supercharging” IP valuation with WACC explains how the weighted average cost of capital combines the required returns of equity and debt investors, adjusted for tax effects and specific risk factors of the IP.

For high-risk, early-stage patents or emerging brands, the risk component is higher; for established, diversified portfolios it is lower. In all cases, the discount rate expresses the trade-off between waiting for future IP benefits and investing in alternative opportunities today.

Tax amortization benefits – the hidden value component

When IP is acquired in an asset deal or a taxable business combination, accounting rules often require the recognition of identifiable intangibles at fair value. These assets can then be amortized for tax purposes over their useful life. The resulting tax amortization benefits (TAB) effectively increase the value of the asset for the buyer, because they reduce future tax payments.

The article on the “hidden value” of TAB walks through this logic and introduces a step-up factor that can be applied to the present value of IP cash flows to reflect the additional benefit.

In the lecture, this is illustrated by calculating discounted amortization rates over a ten-year period and deriving a typical step-up factor of around 1.2, depending on tax rate and WACC.

For IP transactions and purchase price allocations, it is therefore not enough to value the “pure” economic benefits; the tax shield created by amortization must be included as part of the fair value.

The 10-step valuation procedure: from context to model

Valuation is described in the lecture as a craft that combines scientific knowledge, financial modelling, legal understanding and empirical insight. To structure this craft, a ten-step procedure is proposed. It consists of two main phases – analysing the valuation context and designing the valuation model – followed by reporting.

Phase 1: Analysis of the valuation context (Steps 1–4)

- Cause – Why is the valuation needed?

Typical causes include transactions, licensing negotiations, litigation, internal strategy decisions or tax and accounting requirements. Each cause implies different constraints, standards and levels of scrutiny. - Purpose – What role does the valuator play?

The purpose defines whether the valuator acts as independent expert for both parties, advisor to one party, internal analyst or court-appointed expert. It also determines how conservative or advocacy-oriented the work can be. - Goal – What information should the valuation deliver?

In some cases, a point estimate is required; in others, a value range, scenario comparison or sensitivity analysis is more relevant. The goal clarifies whether the focus is decision support, documentation, negotiation or compliance. - Addressee – Who will use the value information?

A valuation for a technical management team can assume deep knowledge of the underlying technology, while a valuation for an external investor or a tax authority must explain assumptions and methods in a different way. Understanding the addressee ensures that the later report is interpretable and auditable.

The output of this phase is a clear mandate: the valuator knows what question is being answered, for whom, and under which institutional and legal framework.

Phase 2: Construction of the valuation model (Steps 5–9)

- Subject matter – What exactly is being valued?

Here the IP asset and the valuation scenario are defined with precision: which patents, which trademark registrations, which territories, what remaining life, and under what exploitation model (e.g. exclusive licence in Europe for medical devices). - Decision situation – Which decision will be informed?

For example, a go/no-go decision on product launch, a choice between licensing alternatives, or the definition of an internal transfer price. The decision situation guides which scenarios and sensitivities are relevant. - Value determination method – How will the value be calculated?

Based on the earlier discussion, the valuator chooses between cost, market or income approach – or a combination. For brands and patents with clear cash-flow impact, income approaches are usually preferred; for early-stage technology or lack of data, cost or market proxies may support the analysis. - Objectification – How is subjectivity controlled?

Objectification means documenting assumptions, using consistent parameter sources, testing alternatives and cross-checking results with secondary indicators (for example, comparing royalty-derived values with observed deal multiples). The goal is not to eliminate judgment, but to make it transparent and reproducible. - Information base – Which data are considered, and with what quality?

This step includes collecting financials, market studies, conjoint analyses, legal opinions on strength and scope, and management plans. It also assesses reliability: are the sales forecasts consistent with historical performance? Are the legal risks of invalidity or infringement addressed?

Together, these steps result in a well-specified valuation model that connects the economic narrative of the IP asset with quantitative cash-flow projections and a justified discount rate.

Phase 3: Reporting (Step 10)

- Report – How is the result communicated?

The final report describes the valuation context, the model choices, the data used, the calculations and the conclusions, including limitations and sensitivities. For complex portfolios, it may also highlight strategic insights: which brands or patents account for most of the value, where legal weaknesses could undermine cash flows, or how different licensing structures would change the result.

A good report does more than present a number. It creates a shared understanding of how IP contributes to value creation, which in turn helps management align IP strategy with business objectives.

Why this matters for IP management

When brands, patents and other intangibles dominate enterprise value, managers cannot treat IP as a purely legal or technical topic. The IP Management Glossary entry on brand and the dIPlex overview on IP valuation both point in the same direction: IP has to be designed, protected and exploited with the financial impact on future cash flows in mind, not just with registration statistics.

Systematic valuation – using clear concepts of value, robust income approaches, correct handling of WACC and TAB, and a transparent 10-step process – turns IP into a language that finance, strategy and marketing can understand together. That shared language is increasingly becoming a prerequisite for credible negotiations, sound investment decisions and responsible reporting in an economy built on intangibles.