The Dynamics of Technological Innovation: CEIPI MIPLM 2025/26 Module 3

Technological innovation is often portrayed as a linear success story: a breakthrough invention, a clever business model, rapid market adoption, and long-term dominance. The reality, as explored in the third module of the Master for IP Law and Management (MIPLM) 2025/26, is far more complex. This module, curated by Prof. Dr. Alexander J. Wurzer and subject matter experts at the IP Business Academy Per Wendin, and Margaux Zyla equips IP experts to unfold through nonlinear dynamics shaped by technological uncertainty, market adoption patterns, organizational capabilities, and strategic intellectual property decisions.

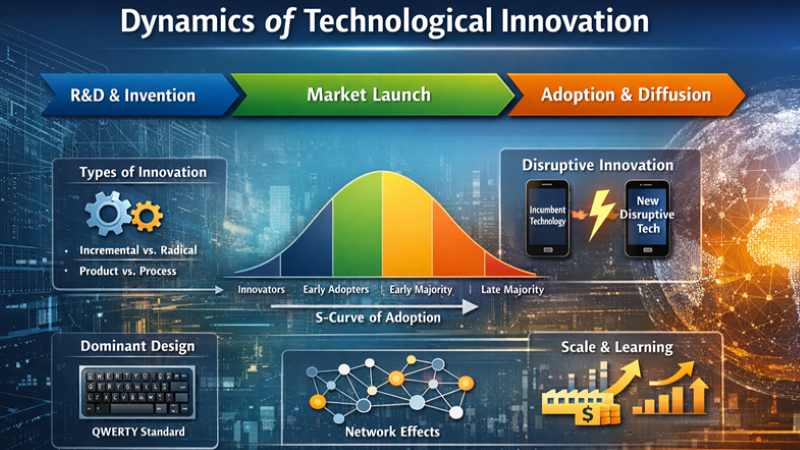

This lecture on the Dynamics of Technological Innovation provides a structured framework for understanding why some technologies transform industries while others fail despite technical excellence, and why IP strategy must evolve across different phases of innovation.

From Invention to Innovation: A Crucial Distinction

A foundational insight of the lecture is the strict distinction between invention and innovation. Inventions are technical or scientific solutions to specific problems, typically originating from R&D activities. Innovations, by contrast, encompass the commercial, organizational, and social processes that transform inventions into market-relevant offerings.

📌 You find the 🔗𝗱𝗜𝗣𝗹𝗲𝘅 digital IP lexicon about IP and Innovation here

This distinction matters because many technologically superior inventions fail not due to weak engineering, but due to flawed commercialization. The Iridium satellite communication system is a canonical example. Developed by Motorola as a technically advanced global satellite phone system, Iridium failed commercially after launch in 1998. Only after relaunching with a radically refocused target market did it become profitable. The invention did not change. The innovation strategy did.

📌 You find the 📑IP Management Letter on Iridium’s Journey here

For IP professionals, this underscores a critical lesson: protecting inventions is not enough. IP strategy must support the broader innovation process, including market positioning, licensing models, and adoption incentives.

Innovation as a Process, Not an Event

The lecture frames innovation as a multi-phase process rather than a single milestone. Three interlinked phases are emphasized:

- R&D and invention development

- Market launch and commercialization

- Adoption and diffusion

Innovation can be defined narrowly, broadly, or in its broadest sense depending on where one draws the boundaries. In its broadest interpretation, innovation continues well beyond market launch, extending into diffusion, learning effects, and incremental improvements. This view challenges simplistic, stage-gate interpretations and highlights why IP lifecycle management must remain adaptive long after filing decisions are made.

📌 You find the entry on Innovation Process in the 🔎𝗜𝗣 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗚𝗹𝗼𝘀𝘀𝗮𝗿𝘆 here

For IP law and management, this means that portfolio decisions made early in R&D may need to be revisited as technologies diffuse, standards emerge, or markets shift.

Innovation as a capability

Types of Innovation and Their Strategic Implications

The lecture systematically differentiates between several types of innovation, each with distinct management and IP implications.

Product innovations introduce new or improved goods that address customer needs, while process innovations improve how goods are produced, often focusing on efficiency, cost reduction, or quality. Importantly, product innovations tend to shape competitive positioning, whereas process innovations reshape internal economics.

Another critical distinction is between incremental and radical innovation. Incremental innovations build on existing knowledge bases and competencies. Radical innovations, by contrast, often disrupt established capabilities and organizational routines. The shift from chemical to digital photography illustrates how radical innovation can destroy existing competencies while creating new competitive landscapes.

The lecture also introduces modular versus architectural innovation. Modular innovation changes components without altering system architecture. Architectural innovation redefines how components interact. This distinction explains why incumbents often fail when system architectures change, even if individual components improve only incrementally.

📌 You find the entry on Modular Innovation in the 🔎𝗜𝗣 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗚𝗹𝗼𝘀𝘀𝗮𝗿𝘆 here

📌 You find the entry on Milestone-Based IP Management in the 🔎𝗜𝗣 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗚𝗹𝗼𝘀𝘀𝗮𝗿𝘆 here

📌 You find the entry on IP Lifecycle Management in the 🔎𝗜𝗣 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗚𝗹𝗼𝘀𝘀𝗮𝗿𝘆 here

Technology Push, Market Pull, and Why Either Alone Is Insufficient

Innovation is often explained through either technology push or market pull narratives. Technology push emphasizes scientific breakthroughs enabling new products. Market pull highlights unmet customer demand as the driver of innovation.

The lecture rejects mono-causal explanations. Successful innovations typically emerge from the convergence of technology push and market pull. Technology push offers high earning potential but high risk and long development cycles. Market pull enables faster realization and lower risk but often limits radical novelty.

For IP strategy, this convergence implies that filing decisions based solely on technical novelty or immediate market demand are fragile. Robust IP planning must anticipate how emerging demand and evolving technology trajectories may intersect over time.

📌 You find the 📑IP Management Letter on Push and Pull Innovation here

Diffusion, S-Curves, and the Limits of Performance

One of the most powerful analytical tools discussed is the technology S-curve. It describes both performance improvement and market adoption over time. Early stages show slow progress, followed by rapid growth, and eventually saturation.

The lecture highlights a critical strategic pitfall: technological performance often exceeds what mainstream customers can absorb. This mismatch creates opportunities for disruptive technologies, which initially underperform on traditional metrics but excel on alternative dimensions such as cost, convenience, or accessibility.

Understanding diffusion categories, from innovators to late adopters, helps explain why early market feedback can be misleading. Lead users and early adopters are particularly valuable signals for future trajectories, even if they represent small or initially unattractive markets.

📌 You find the entry on Milestone-Based IP Management in the 🔎𝗜𝗣 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗚𝗹𝗼𝘀𝘀𝗮𝗿𝘆 here

S-curves in innovation

Disruptive Innovation and the Innovator’s Dilemma

Building on Christensen’s framework, the lecture explores why dominant firms struggle with disruptive technologies. Disruption often begins in small, low-margin markets that fail to meet the growth expectations of established organizations. As a result, incumbents rationally ignore them.

Five core principles explain this failure, including resource dependence on existing customers, organizational capabilities defining disabilities, and the impossibility of analysing non-existent markets using traditional tools.

From an IP perspective, disruptive innovation challenges conventional portfolio logic. Patents optimized for sustaining technologies may offer little protection or strategic value when new performance dimensions redefine competition. IP professionals must therefore recognize when separation, spin-offs, or alternative IP exploitation models are necessary.

Disruptive Technology

The Emergence and Power of Dominant Designs

A central theme of the lecture is the concept of dominant design. A dominant design defines what a product is supposed to look like and how it should function. Once established, it drastically reduces uncertainty, standardizes expectations, and shifts competition from product features toward cost, scale, and process efficiency.

The QWERTY keyboard is a classic illustration. Despite technically superior alternatives, switching costs, learning effects, and complementary investments locked the market into QWERTY. Dominant designs persist not because they are optimal, but because they align technological, economic, and social forces.

Dominant designs reshape industries. They reduce the number of firms, stabilize product architectures, and increase the importance of process innovation. For IP management, this phase often marks a transition from exploratory protection toward portfolio consolidation, standard-essential strategies, and licensing.

Economics of Dominant Designs and Network Effects

Dominant designs are reinforced by learning effects, economies of scale, and network externalities. The larger the installed base, the more attractive the technology becomes for users and producers of complementary goods. This feedback loop accelerates lock-in and increases switching costs.

Regulation, strategic maneuvering, and producer-user communication further influence which design becomes dominant. Importantly, dominance is not purely technological. Brand reputation, complementary assets, and timing play decisive roles.

For IP professionals, this highlights why legal protection must be aligned with ecosystem dynamics. Patents, design rights, and complementary IP tools gain value not in isolation, but through their role in reinforcing or leveraging dominant designs.

Dominant Design

Implications for IP Law and Management Education

The Dynamics of Technological Innovation lecture demonstrates that IP management cannot be reduced to filing strategies or legal enforcement. It is a dynamic, strategic discipline deeply intertwined with innovation processes, market structures, and organizational behaviour.

For students in the Master for IP Law and Management, the key takeaway is clear: effective IP professionals must understand when technologies are emerging, how they diffuse, and why dominant designs stabilize industries. Only then can IP tools be deployed not just defensively, but as instruments of strategic positioning, coordination, and long-term value creation.

Innovation is not about predicting the future with certainty. It is about understanding its dynamics well enough to make informed, adaptive decisions under uncertainty.