From Nuclear Standoffs to Patent Races: What Game Theory Teaches Us About IP Strategy

Game theory was born in the context of war, markets and competition – situations where outcomes depend not only on what you do, but also on what others decide at the same time. In modern IP strategy, this is the daily reality: competitors react to your filings, licensing offers, litigation threats and standards activities. Understanding game theory means understanding how these strategic interactions shape the value of patents, brands and technology portfolios. This post is a summary of the lecture on Game Theory from the Master Program of IP Law and Management at CEIPI.

The MIPLM skills training on “Decision in IP Business” introduces game theory exactly from this angle: as a toolkit to describe strategic interactions, test their internal logic and identify stable outcomes between rational players.

What game theory is – and why it matters for IP

Game theory is the economic analysis of situations where several “players” (firms, states, inventors, platforms) make decisions whose outcomes depend on each other. A game is defined by:

- the players involved

- the strategies available to each player

- the payoffs (profits, losses, years in prison, market share) for each combination of strategies

In IP, this framework fits many familiar questions:

- Should we start a patent race or keep protection lean and focused?

- Do we threaten litigation or negotiate a quiet cross-licence?

- Do we join a standard and license under FRAND, or stay outside and try for proprietary control?

- Do we keep technology as a trade secret or publish and patent?

Game theory gives all of this a precise language. It allows IP managers to translate informal “what if” discussions into explicit strategy tables and decision trees, and to test whether the chosen strategy is actually rational given what others can do.

A brief historical arc – from MAD to markets

The popular history of game theory often starts in the Cold War. The short documentary “Game Theory – MAD” explains how strategists used simple models to analyse nuclear stand-offs and the logic of deterrence, especially the concept of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). In this setting, each superpower had enough nuclear weapons to destroy the other – and both knew that a first strike would trigger retaliation.

In a MAD scenario:

- Each side has two strategies: attack or don’t attack.

- If one attacks and the other does not retaliate, the attacker wins.

- But if both attack, both are destroyed – the worst possible payoff for everyone.

Because both sides understand this, the credible strategy is not to attack, but to signal willingness and capability to retaliate. The logic of MAD is paradoxical: stability through guaranteed catastrophe. Yet it captures the core game-theoretic idea that the threat of an action can be more important than the action itself.

Over time, game theory moved from military strategy into industrial organization, antitrust, auctions, contract design and innovation. Today it is central in analysing platform competition, standardization battles, licensing in patent pools and co-operation between rivals.

Strategic interaction in IP: the language of games

The slides introduce game theory as the analysis of strategic interaction: situations where each player knows that outcomes depend on everyone’s decisions – and knows that the others know this, too.

Two basic game forms are especially relevant to IP:

- Static (simultaneous) games in normal form, where players choose strategies at the same time without communication and we record payoffs in a payoff matrix. Patent races and simultaneous licensing decisions often fit this format.

- Dynamic (extensive form) games, where decisions follow in sequence, represented as a game tree. Litigation, licensing negotiations or sequential patent filings are best modelled this way.

Once a situation is framed as a game, we can ask: Which strategies are irrational? Which outcomes are stable? Where is co-operation possible, and when does competition trap everyone in a bad equilibrium?

The Prisoner’s Dilemma and IP: why rational players may over-patent

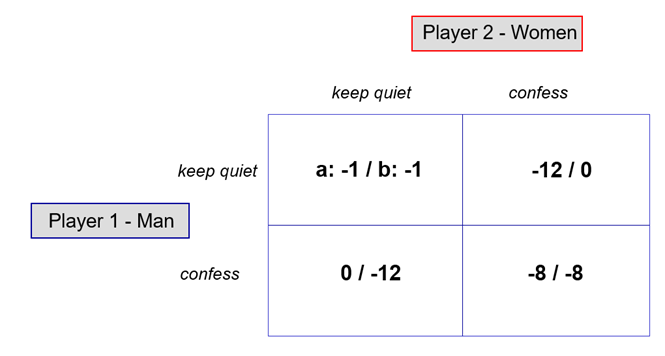

The classic entry point is the Prisoner’s Dilemma, nicely visualised in the explainer “The Prisoner’s Dilemma – Game Theory 101”. In the lecture, the story is told with two suspects in separate cells who must decide whether to confess or keep quiet.

The structure is:

- If both keep quiet, each gets a minor sentence (−1 / −1).

- If both confess, each gets a medium sentence (−8 / −8).

- If one confesses and the other keeps quiet, the confessor goes free (0) and the other receives a very harsh sentence (−12).

For each prisoner, confessing is the better strategy no matter what the other does:

- If the other keeps quiet, confessing gives 0 instead of −1.

- If the other confesses, confessing gives −8 instead of −12.

Confessing is a dominant strategy. Rational prisoners will both confess, even though this leads to −8 / −8 – worse for both than the −1 / −1 they could have had with mutual silence.

In IP strategy, many situations share this structure:

- Two firms in a technology field might both be better off with moderate patenting, but each has an incentive to expand filing aggressively to block the other.

- Two SEP holders could both benefit from moderate royalty rates, but each has an incentive to push rates up while hoping the other stays moderate.

The result can be over-patenting, excessive litigation or mutual value destruction, even though all players could be richer under co-operative restraint.

Dominated strategies and iterated elimination

The lecture then introduces dominated strategies: a strategy is strictly dominated if another strategy always gives a better payoff, regardless of what opponents do.

In the Prisoner’s Dilemma, “don’t confess” is strictly dominated by “confess” for both players – it is never the best response. A rational player will never use a strictly dominated strategy.

The video “A Game of Elimination – Solving the Puzzle” illustrates how we can iteratively eliminate dominated strategies from a payoff matrix:

- Look at the game from one player’s perspective and remove any strategy that is strictly worse than another across all columns.

- With those gone, re-evaluate the remaining strategies for the other player.

- Repeat until no dominated strategies remain.

In the slides, this procedure is applied to an appropriation race between two firms choosing between patenting, secrecy and lead time. Some strategies (such as a weak lead-time approach) are dominated and can be eliminated; what remains is a logically reduced game where only potentially rational strategies survive.

For IP managers, this is more than an academic trick. It is a way to:

- Spot obviously inferior IP strategies that should never be on the table.

- Clean up complex decision spaces before performing more detailed valuation or scenario analysis.

Nash equilibrium: when no one wants to move

The next key concept is the Nash equilibrium, named after John Nash and popularised by the bar-scene in “A Beautiful Mind”, often used in the video “Nash Equilibrium – Game Theory Explained”. In the slides, Nash equilibrium is defined as a strategy profile where no player can improve their payoff by unilaterally changing strategy, given what the others are doing.

Important points:

- Every game does not necessarily have a dominant strategy, but most finite games have at least one Nash equilibrium (perhaps in mixed strategies).

- A dominant-strategy outcome, like mutual confession in the Prisoner’s Dilemma, is always a Nash equilibrium – but many Nash equilibria involve no dominant strategy.

For IP, Nash equilibria describe stable patterns of behaviour:

- In a patent race, both firms filing heavily might be an equilibrium: no single firm can cut its patent budget without losing competitive position, given that the other continues filing.

- In SEP licensing, a pattern of cross-licensing at certain rates can be an equilibrium: no participant can gain by unilaterally changing royalties while others keep their offers.

The concept warns us that equilibrium does not mean optimality. A Nash equilibrium can lock firms into wasteful patent wars, just as it can maintain mutually beneficial licensing arrangements. Understanding where the equilibrium lies is the first step to changing the game. Here is the move scene:

Static vs dynamic games: from payoff matrices to litigation trees

The lecture contrasts normal-form (static) and extensive-form (dynamic) games. Static games model situations like the Prisoner’s Dilemma, where choices are simultaneous and players do not respond to each other during the game. Extensive-form games show sequential decisions in a tree:

- First, one party files a broad or narrow patent.

- Then, a competitor decides whether to oppose, settle or wait.

- Later, a court decides on validity or infringement.

Here, game theory uses backward induction: “look ahead and reason back”. Players analyse the likely reactions at future nodes and choose their current strategies accordingly.

This is directly relevant to IP litigation and licensing:

- A firm may file an opposition not because it expects to win, but because the threat of delay and cost changes the settlement branch of the tree.

- A patentee may invest in a very strong first case to shape the expectations of future defendants, influencing the whole litigation game in the industry.

Patent races and appropriation games

The slides give two classic IP applications.

1 . Patent race in fertilizers

Two companies, ChemBio and FSAB, decide between massive patenting and low patenting. If both patent heavily, each gets a moderate NPV (200). If both stay low, each earns 400 – the best joint outcome. But if one patents massively while the other stays low, the aggressive filer earns 500 and the other only 100.

Here, “massive” becomes a best response to any expectation that the rival might patent aggressively. The Nash equilibrium is mutual over-investment in patents, even though both would profit more from restraint – a direct analogue of the Prisoner’s Dilemma.

2 . Appropriation race with patenting vs secrecy vs lead time

The appropriation race example contrasts strategies like patenting, keeping technology secret or relying on lead time. Iterated elimination of dominated strategies simplifies the game and reveals that patenting can be a rational equilibrium choice when competing against secrecy or lead time, especially when legal enforcement is credible.

These examples show why IP portfolios often grow beyond what a pure valuation of isolated patents would justify: firms respond to the game they are in, not just the net present value of a single invention.

From rivalry to co-operation: co-opetition between Apple and Microsoft

Game theory does not end with conflict. It also explains why rivals sometimes become partners – a strategy often described as co-opetition: competing on some dimensions while co-operating on others.

The video “Apple & Microsoft – Solving the Mystery” and the blog article on co-opetition analyse how two of the fiercest rivals in tech have long maintained a pattern of selective collaboration.

Key elements of this co-opetition game include:

- Selective openness: Microsoft provides Office and cloud services on Apple devices; Apple ensures that its hardware is a high-quality platform for those services. Instead of excluding each other, both firms adopt platform strategies where mutual compatibility enlarges the overall market.

- Cross-licensing and IP sharing: Over the years, Apple and Microsoft have settled major disputes through cross-licensing agreements that give each firm predictable access to critical patents while reducing litigation risk. IP here is both weapon and peace treaty.

- Strategic separation of battlefields: Each firm focuses on its strengths – Apple on integrated hardware-software ecosystems, Microsoft on productivity software and cloud infrastructure – while co-operating where their interests align.

In game-theoretic terms, co-opetition restructures the payoff matrix:

- Pure rivalry might resemble a Prisoner’s Dilemma with over-investment in litigation and incompatible ecosystems.

- By opening interfaces, cross-licensing and aligning on some standards, the players create a new game where mutual co-operation can become a Nash equilibrium with higher payoffs for both.

For IP strategy, this shows that licensing, standards participation and technology sharing are not signs of weakness. They are tools to change the rules of the game – moving from mutually destructive races to sustainable ecosystems where all core players earn more.

Why IP professionals need a game-theoretic mindset

The lecture concludes with a simple set of rules adapted from Dixit and Nalebuff: look ahead and reason back; use dominant strategies when you have them; eliminate dominated strategies; and search for Nash equilibria.

For IP professionals, adopting this mindset means:

- Seeing patenting, secrecy, licensing and litigation not as isolated decisions, but as moves in an ongoing game.

- Recognising when your portfolio strategy is stuck in a Prisoner’s Dilemma and exploring co-operative arrangements that change the matrix.

- Designing contracts, cross-licences and standards participation so that co-operative outcomes are equilibrium outcomes, not fragile gentlemen’s agreements.

In a world of overlapping portfolios, platform ecosystems and global patent races, game theory is no longer a mathematical curiosity. It is an essential lens for understanding how IP strategies interact – and how, by changing the game, you can create more stable, more valuable positions for the businesses you support.