When Secrecy Enters the Courtroom: What Judges Really Expect in Trade Secret Cases

Trade secrets have become the quiet heavyweights of IP. They are the formulas, process know-how, customer lists, pricing logics and data structures that keep many businesses ahead. But the moment these assets are at stake in court, one brutal reality emerges: a trade secret is only as good as the evidence you can show a judge.

This article builds on the recent 🖥️IP Business Talk with trade secret litigator Dr. Axel Oldekop, his digital IP lexicon 🧭dIPlex guide on Litigation of Trade Secrets, and his episode of the 🎧IP Management Voice podcast “Litigation and Protection of Trade Secret”. Together, these perspectives form a very practical message: courts are less impressed by big words about “confidentiality” and far more interested in the boring details of access rights, contracts, logs, training, and incident response.

Summary of the 🖥️IP Business Talk with Dr. Axel Oldekop

From “we don’t talk about it” to a legally recognised asset

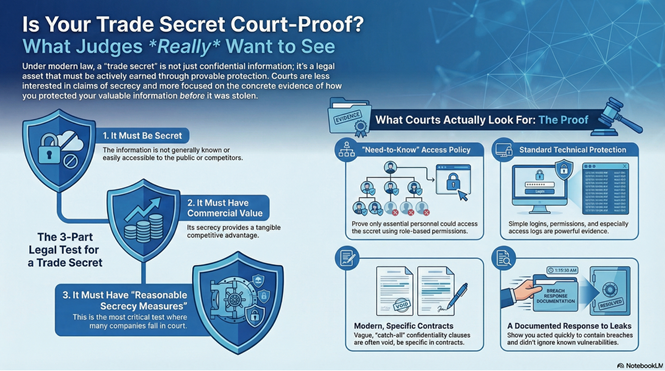

Many companies still think a trade secret is created simply by not talking about it. Under modern European and German law, that assumption is wrong.

The EU Trade Secrets Directive and its implementation in the German Geschäftsgeheimnisgesetz (GeschGehG) created a unified framework: information is only a protected trade secret if it is secret, has commercial value because of that secrecy, and is subject to reasonable secrecy measures. This logic is unpacked in Oldekop’s dIPlex article on The Three-Part Test: Defining a Trade Secret.

In other words: secrecy is no longer just a factual situation (“we never published it”), but a legal status that must be actively earned and demonstrated. Since April 2019, there is no transitional comfort. If you cannot show objective secrecy measures, you simply do not have trade secret protection – no matter how important the information feels internally. That shift is what now shapes court expectations.

The three-part legal test: what counts as a trade secret?

Oldekop’s three-part test translates the legal definition into something practitioners can actually use:

- The information must be secret

It must not be generally known or readily accessible to people who usually deal with that type of information. This does not mean nobody else can know it; it means it is not public knowledge or easily found in patents, brochures, websites, or obvious public sources. - It must have commercial value because of its secrecy

The information needs to make a competitive difference because it is not widely known. A customer list, an unpatented formula, specific process parameters, or a sourcing strategy all qualify if competitors would gain an advantage from them. - It must be subject to reasonable secrecy measures

This is where many companies fail. The law expects concrete organisational, technical, and/or contractual measures – and the ability to prove them. “We always treated it as confidential” is not enough.

As Oldekop explains in the dIPlex series on Litigation of Trade Secrets, these measures are not an optional extra; they establish the trade secret in the first place. Without them, there is no protection to litigate.

What courts actually look for: Oldekop’s “three prongs”

In practice, German civil courts have not yet developed a rigid standard catalogue of measures, but they tend to be surprisingly pragmatic. Drawing on his litigation experience, Oldekop points to three prongs that usually are a good starting position for the trade secret owner in court.

Need-to-know as a guiding principle

Judges want to see that only those people who really need a piece of information to perform their work have access to it. That means:

- Role-based access for teams like R&D, production, or key account management

- No company-wide “open shares” containing sensitive manufacturing data or customer lists

- Ideally, a documented access policy that maps roles to access rights

A written policy is excellent evidence, but as Oldekop notes in the podcast “Litigation and Protection of Trade Secret”, a credible IT or security witness – the person who configured the network and access rights – can already make a strong impression.

Technical protection: simple is fine, but it must exist

Courts are not waiting for quantum-proof encryption. They look for reasonable technical measures, like:

- Login requirements for networks, databases, and document management systems

- Role-based permissions (who can view, edit, export)

- Separation of sensitive information from general file shares

- Log files that show who accessed what, when

A properly configured standard system such as Microsoft 365 with differentiated access rights is usually perfectly adequate. The decisive question is whether you can later show how access was restricted in practice – not whether you had the fanciest security hardware.

Contractual instruments: yes, but with modern wording

Confidentiality provisions in employment, supplier, and customer contracts remain essential. They demonstrate that the company treats certain categories of information as secret and expects partners and staff to do the same.

However, recent decisions of the German Federal Labour Court have made one thing clear: broad “catch-all” confidentiality clauses (“everything you ever see here is confidential”) can be void because they restrict employees disproportionately. As the dIPlex article on Documenting Trade Secrets in a Legally Compliant Manner explains, clauses should specify at least categories of confidential information – technical know-how, customer lists, pricing strategies – instead of trying to cover everything in one sentence.

If a company still relies on old, overly broad clauses, it risks standing in court with a contract that does not count.

Logs, leaks and misappropriation: evidence beyond access measures

Secrecy measures are only half the litigation story. The other half is misappropriation: did the defendant actually access and use the secret?

Here, detailed access logs can become decisive. If a company can show that “Employee X accessed File Y on Date Z and exported it”, the story becomes very concrete. In both the IP Business Talk and the podcast, Oldekop emphasises that logs are important not only to show that protective measures existed, but also to link a specific person to a specific act of access.

Courts also observe how a company reacts to leaks. Two patterns are particularly relevant:

- Acute threat: when a partner announces a trade fair presentation of a jointly developed product or when an ex-employee is about to use stolen know-how, companies must act fast. The dIPlex article From Theft to Court: Legal Options shows why preliminary injunctions become crucial to prevent the one thing that ends protection forever: public disclosure.

- Known vulnerabilities: if management knows that passwords circulate freely or that a serious data leak exists and does nothing for a long time, courts will question whether the information was truly treated as a secret. In extreme cases, this can destroy trade secret status.

Log files and incident response are therefore not just IT hygiene; they are part of the evidentiary foundation of a future lawsuit.

Distinguishing real secrets from “alleged” ones

Oldekop repeatedly distinguishes between “good” and “bad” trade secrets in his explanations.

A bad trade secret is something that is marketed internally as highly confidential, but in reality:

- Can be reconstructed by simply looking at the product

- Has been broadly disclosed in marketing materials

- Is accessible to almost everyone in the organisation

A good trade secret often has one of two characteristics, as described in The Three-Part Test: Defining a Trade Secret:

- Process know-how that is not visible in the product

For example, production parameters, material formulations, or specific calibration sequences. These can remain secret even when the product is on the market. - Curated data combinations

A classic case is the internal customer list: each individual data point (company name, address, past purchases) may be accessible from public or semi-public sources. But the curated aggregation – plus knowledge of timing, purchasing patterns, and upcoming needs – is what forms the actual trade secret.

The same logic now applies in the age of AI. Using a public AI tool to discuss a proprietary production process may expose too much and undermine claims that the information was carefully protected. But the fact that an AI can discover certain information through public data does not automatically mean a company’s specific application of that information ceases to be a secret. The key legal question is what exactly was disclosed and whether the combination and use inside the company remained secret.

From theft to court: the litigation toolbox

When things escalate, companies need a clear picture of their enforcement options. In From Theft to Court: Legal Options, Oldekop sets out the main pillars.

Civil proceedings under the GeschGehG

For most companies, civil litigation under the GeschGehG is the main route. Core instruments include:

- Injunctions – standard and preliminary – to stop acquisition, use, or disclosure

- Removal and destruction of data carriers, documents, and products created with the stolen know-how

- Information claims to uncover the scope of the breach and the chain of use

- Damages, potentially calculated based on lost profit or a hypothetical licence fee

Remedies are “IP-like”: courts can order destruction of products, recall from the market, and far-reaching prohibitions, very similar to patent infringement cases. That is why accidentally importing a competitor’s trade secrets via new hires can be disastrous.

Criminal law and unfair competition

Depending on the facts, companies can also resort to criminal prosecution or claims under the German Act Against Unfair Competition. These routes can deter egregious behaviour and add pressure, but they also involve higher evidentiary burdens and are slower to control acute disclosure risks. In practice, many strategies combine civil proceedings for fast injunctive relief with selective criminal complaints in particularly severe cases.

Building a “court-proof” documentation system

One of the strongest messages from the dIPlex article Documenting Trade Secrets in a Legally Compliant Manner is almost cruel in its simplicity: in court, the first question is not “What did the infringer do?” but “What did you do to protect this information?”

A credible system has at least these elements:

- Identification and classification

- Systematic audit of potential secrets across R&D, IT, sales, production, HR

- Inventory of information that meets the three-part test

- Sensitivity classes (“Top Secret”, “Confidential”, etc.) that map to different protection levels

- Mapped measures for each class

- Technical: access controls, encryption where appropriate, structured storage

- Organisational: need-to-know, clear ownership, defined responsibilities

- Contractual: NDAs, tailored employment clauses, supplier/customer provisions

- Documentation and approval

- A master log of trade secrets, their classification, and responsible owners

- Policy documents on access, incident handling, onboarding and offboarding

- Regular management sign-off and updates

- Training, onboarding, offboarding

Training staff on what counts as a trade secret, how to treat information that new employers bring along, and what is forbidden reduces risk and shows courts that the company is not trying to profit from others’ secrets. - Incident management

Companies need documented procedures for handling suspected leaks or breaches: detection, containment, escalation, documentation, and corrective measures. Passivity after discovering a serious vulnerability is one of the fastest ways to undermine later litigation.

Thinking globally: EU, US, China

Trade secrets are not just a European topic. In Protecting Trade Secrets Worldwide, Oldekop compares the frameworks in the EU, United States and China.

- European Union: harmonised by the Trade Secrets Directive. The core definition (secret, commercial value, reasonable measures) and civil remedies (injunctions, destruction, damages) are aligned across member states, even though enforcement cultures still differ. Whistleblower protections are strong and can override trade secret claims in the public interest.

- United States: a dual system with state-level laws under the Uniform Trade Secrets Act and the federal Defend Trade Secrets Act. The federal route allows nationwide injunctions, which is particularly relevant for cross-border cases.

- China: a rapidly evolving system where trade secret protection has been strengthened in recent years as part of broader IP reforms. For foreign businesses, practical enforcement remains challenging, but the direction of travel is clearly towards more robust protection.

For global companies, this means that the definition of reasonable measures converges internationally – access control, contracts, logs, training – but specific procedural options and enforcement intensity still depend on the jurisdiction.

A practical checklist: what judges really want to see

Putting the IP Business Talk, the 🎧IP Management Voice episode and the full dIPlex series on Litigation of Trade Secrets together, a company that wants to be taken seriously in trade secret litigation should be able to show at least the following:

- Clear definition and classification of its key secrets

- A documented need-to-know access concept, implemented in real IT systems

- Concrete technical measures (logins, permissions, log files) for sensitive information

- Specific and up-to-date confidentiality clauses in employment and third-party contracts

- Training and HR processes that address trade secrets in onboarding and offboarding

- Evidence of timely reaction to leaks, vulnerabilities, and imminent disclosures

- A thought-through litigation strategy, including the use of preliminary injunctions where necessary

- Awareness of international differences, especially when secrets or misuse cross borders

Trade secret litigation is not about theatrical courtroom moments. It is about showing that, long before the conflict, the company treated its know-how as a structured, documented, actively managed asset.

When secrecy enters the courtroom, judges are not looking for magic. They are looking for proof that you behaved like a responsible owner of your most valuable knowledge – long before anyone tried to steal it.

Here you get access to the recording of this fascinating live Interview:

👉 IP Business Talk with trade secret litigator Dr. Axel Oldekop